Interview by Laura Netz

Designer and multimedia artist Rehab Hazgui explores experimental electronics and biohacking through electromechanical sound installations and live performances involving handmade audio devices and modular synthesisers. Born and based in Tunisia, she is active in community initiatives and considers Do It Yourself (DIY) culture and digital creation as mediums for civic action.

Rehab uses handmade instrument design in self-made devices such as YELLO (2016), a prototype she built which is a noise synth and an analogue video mixer with dual oscillators, a waveshaper, a square wave LFO, and two inputs for video. For the past six years, Rehab Hazgui runs workshops for young people and adults, encouraging the exploration of noise, sound and music.

She is working to provide creative and imaginative activities in an accessible, fun and educational way. Using a wide variety of analogue and digital equipment, her activities include sculpting sounds using small modular synthesisers, composing original experimental sound art, circuit bending, field recording, preparing and building pianos, sound walks, or learning about acoustic ecology.

Convinced by the Do It With Others (DIWO) culture, in 2013, Rehab Hazgui was involved in the foundation of El Fabrika, a Tunisian platform for experimental arts, alternative design, research and activism. For three years, El Fabrika functioned as a Restart Party, a repair community project with origins in London, which aim is to fight planned obsolescence in consumer electronics.

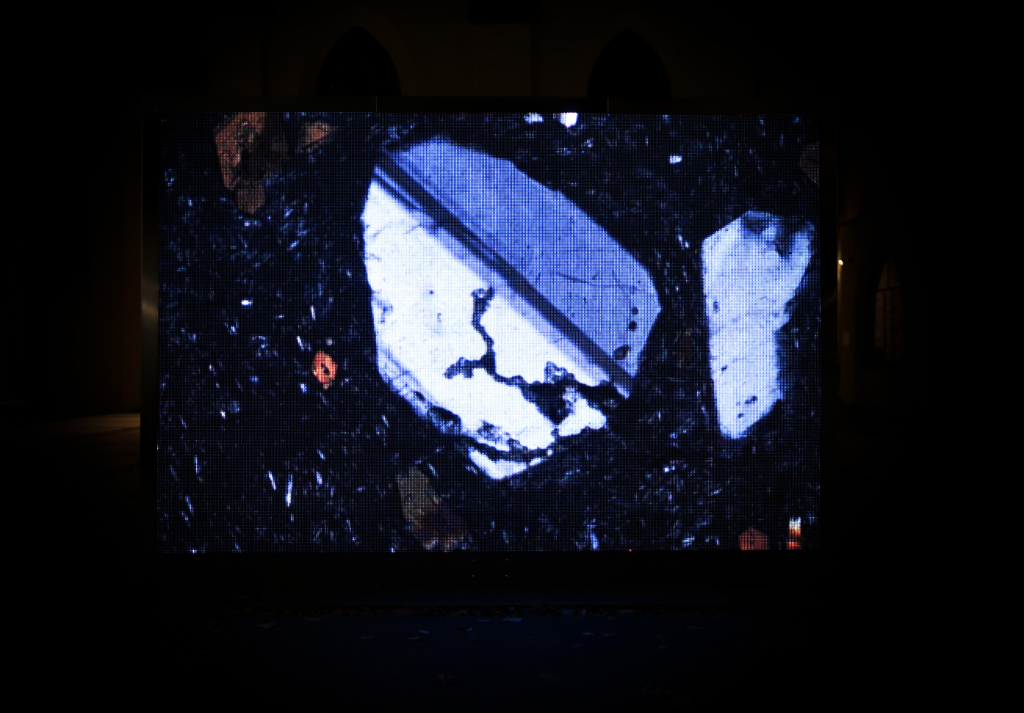

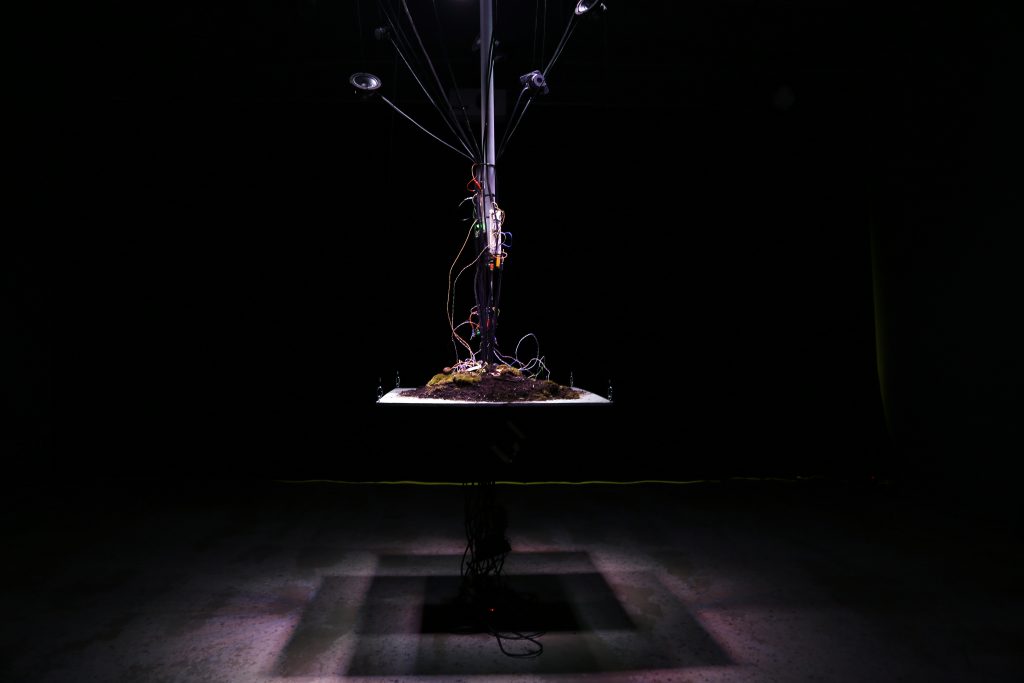

In Sea Moss Trea (2015) the artist reflects on creation in music using sound objects instead of harmony and melody. The relation between human/non-human is expressed as well in her practice. More recently, the work Tilawa has developed, consists of the Quran’s recital emphasising the work’s physical/non-physical aspects. It aims to ‘calligraph’ passages of the Quran in ancient Kufic script, using fungal growth as ink, and ‘recite’ these passages by sonifying the intra-fungal communication during the growth process.

Last year, Rehab Hazgui participated at Phonetics – Sound Fest (2018) in Algiers. The festival’s first edition in Algeria focused on national and international artists consisting of a residency, an exhibition and concerts. Before the festival and for two weeks, Phonetics offered invited artists a residence to create in situ, in collaborative creation, under the same creative space. The experimental results were exhibited in conferences, concerts, performances, and installations.

Rehab Hazgui’s artistic interests are located in the cross-section of art, science and technology, resulting in a combination of technology, biology, experimental electronics, biotechnology, electronics and music expressing the relation between human/non-human in society. Her research engages with philosophical questions concerning the technological manipulation of living matter, and the outcome includes practice-based investigations, participatory facilities based on processes, programmed conceptual structures and workshops for adults and kids.

You started as a motion graphic designer and 2D Animator, but now your work revolves around interactive art, sound, installations, and hacking electronics. How and when do the interests in these disciplines come about?

I graduated from the National School of Design in Tunis as a Visual designer. I started working in Animation in 2008. Then gradually, I started exploring Media Arts practices and concepts across various media, including moving images, still images, audio, and performance. In this context, I have always explored design as visual communication. I concluded that design has always been historically linked with (media) technology and started to question the future of this relationship and what impact technology has on the way we think and process information.

Computer systems offer ways to create but can retard creativity. Many artists believe that the next tool will improve their art; this is particularly problematic in music too. Since then, I naturally began to discover new practices and experience design at the intersection of science, art and technology. This curiosity led me to get involved in the Pixelache, a Finnish interdisciplinary festival that explores bio-arts, alternative economy cultures (Maaland), and experimental electronics (Koelse). From there, I started my journey.

Could you tell us about your more recent project (not phonetics) and the intellectual process behind it?

I recently finished writing a research project, Tilāwa, that has been germinating in my mind for a few years now. I have to admit that it was a big relief to put it down on paper. In my artistic research, I consider art, science and technology as uncontained spaces of discovery and creation, and my interest goes toward critically exploring the limits and definitions of art, science and technology. Over the last five years, my artwork has focused on sound… I have a profound adoration for Sound.

Sound is wonderful and powerful because, different from sight (which is also beautiful, of course), sounds connect things, and sound accommodates many voices simultaneously, and they remain intelligible. Whereas with sight, we see one object and rarely do we actually have transparencies and reflections.

Sound as a medium aesthetically allows us to experience the environment as connections between living things, cycles and rhythms. The Sea Moss Tree (2015) translates my opinion that music should not be limited to traditional parameters such as harmony and melody but more as the organisation of sound objects (notes, pitches, frequencies, recorded/synthesised sounds) in a three-dimensional space throughout a set period of time, and where human and non-human elements can interact together and/or separately, pushing the music-making process beyond conventional bounds.

Similar to The Sea Moss tree project, Tilāwa (which in Arabic is the recitation of the Qur’an and reflection on it) is conceived as a deeper understanding of life as a material, dynamic, and excessive force of transformation that bridges the divide between the physical/virtual, living/non-living, organic/inorganic, human/non-human. It also reflects on the relationship between philosophy and science, as they belong to a common intelligence but differ radically from each other.

Tilāwa aims to ‘calligraph’ passages of the Quran in ancient Kufic script, using fungal growth as ink, and ‘recite’ these passages by sonifying the intra-fungal communication during the growth process.

In this research, I present an interdisciplinary approach to considering how non-human actors make choices and potentially express creativity in their actions in ways not accounted for by conventional Western schools of science and philosophy. I like using purely scientific research methods to ask fundamental questions regarding ontology, logic and philosophy of language. Tilāwa opens up a conceptual space where novel questions about the interrelatedness between non-human agencies can be asked.

You’ve recently been one of the artists in residence at the Phonetics festival, a pioneering festival in the city of Algiers, where you performed and also run 2 workshops. What was the project you developed there? Was it something related to communication (language), sound and technology? Also, Could you tell us about your whole experience there? What was the idea you had in mind before the festival, and what was you found during the 15 days of residence and festival?

Phonetics was a deep dive experience, an encounter where artists, musicians, performers and producers worked on parallel, shared projects, influencing each other in a very convivial frame. During the residency, we were busy living and working together non-stop. The atmosphere was of pleasant excitement and discovery.

We came out with inventing new tools and strategies for improvised play. Our collaborative performance at the IFA (Institut Français d’Alger) was a journey into deep listening, you try and listen to everything, and when you perform, you’re informed by the entire sound environment. Not only what you’re doing, what other people are doing, but the sound of what you’re doing in the room, the acoustics of the room, the environmental sounds, everything.

This is one thing that I like when I perform using a modular synthesiser. You use your intuition to let that all that information inform what you’re playing. During the performance, I felt that the audience sincerely wanted to understand what is being communicated. Our minds are always searching for familiar sounds, words and ways to group to try to make sense of what is being communicated.

From that perspective, I think putting people in situations where their minds and perception capabilities are put to work and challenged was really interesting and healthy. From confusion comes clarity, and then the cycle continues. From that perspective, knowing your perception capabilities, which are used to describe the environment, is irrelevant. You will have a different relationship with that world.

On a different note, I think that this collective performance was, without any doubt, proof that we can work together rather than compete for resources and that adaptation is the mechanism by which we can deal with adversity. We became resourceful and made something new by responding to the conditions around us. I found this initial possibility to think together extremely precious, and somehow I’m convinced that’s the key to the success of Phonetics.

You are also co-founder of El FABRIKA, a platform for experimental art, alternative design, and activism based in Tunisia. What are the aims of this project?

El Fabrika was founded in 2013. This project aims to create and explore the relationship between art and society, practices based on open and collaborative tools, low technology and a “do it yourself” culture. For over than 3years, El Fabrika worked as ….. in the Tunisian scene through El Fabrika Restart Project, a people-powered platform for change, helping demand emerge for more sustainable, better electronics. On a monthly basis, a multifaceted group of people brought their practice and expertise to different locations in Tunis (schools, cafés, bars, restaurants, museums etc..).

The project aimed to encourage a peer-based learning environment related to hacking electronics, appropriate renewable energy production/usage technology, digital fabrication and re/up-cycling materials. This project is a common objective with The Restart Project London, to co-produce a model for artefacts/events taking place in the different partner countries with sustainability as the core goal.

The organisers of Phonetics highlighted how challenging is to develop artistic projects in Algeria. How is the scene in Tunisia? What are the main challenges you face when developing and presenting your artwork?

In Tunisia, I’m best known as the producer of cultural events, grassroots community organisation and alternative pedagogy. And probably the one who always does interesting things outside the sphere of tradition. My identity changes somewhat depending on the social and/or professional environment. On a very personal level, when I’m in Tunisia, I feel isolated most of the time. I think that is just part of trying to do something a bit different as an artist and/or my preference of working on the edge and between artistic expression, science, and technology.

So one of the challenges I’m facing all the time is that my work is not easy to handle aesthetically and familiarly. It is usually located in a grey area between art and science. It therefore requires the viewer to deal with both the medium used and the either critical, positive, utopian or shocking topics of ontology, logic and the staging of “aliveness” in a philosophical, epistemological or ironic way.

Where would you like to take your work into?

Sorry, that’s a tough question.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Hmmm… I would say Fear.. that kind of fear that is always triggered by creativity and by thinking of new ideas. Creativity requires entering into realms of uncertain outcomes… So it’s always a bit scary at first, but once I’m there and aware of the process, creativity turns into innovation.

You couldn’t live without…

Apart from biological needs? Definitely: Silence.