Text by Anne Murray

Memories are constructions. We build them out of fragmented details. These details can be found in different parts of the brain; in accordance with our current objectives, we recreate the topical version of a past event. This text by the artist is printed alongside model 15 of Zsolt Asztalos’s Memory Models’ Exhibition at the Kiscelli Museum in Budapest. Model 15 comprises a series of frames, each shaped differently as if the geometry of thought has changed with the passing of time or reflection.

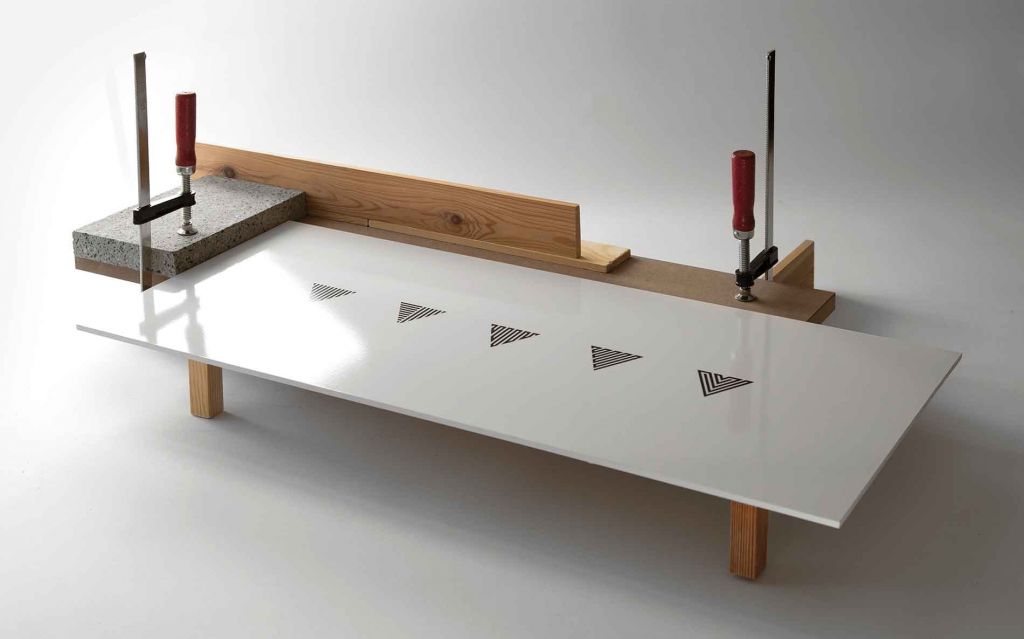

In this model, a small square frame of wood is balanced within another larger square frame, each crossing at right angles to create a plus sign when viewed from above. Underneath these frames, two parallel tracks of wood linearly connect them, as if they are on a railroad or are part of a timeline with an octagon-shaped frame at the end. The octagon shouts ‘STOP’ to us from its empty frame, a semiotic habit of daily traffic signs invades.

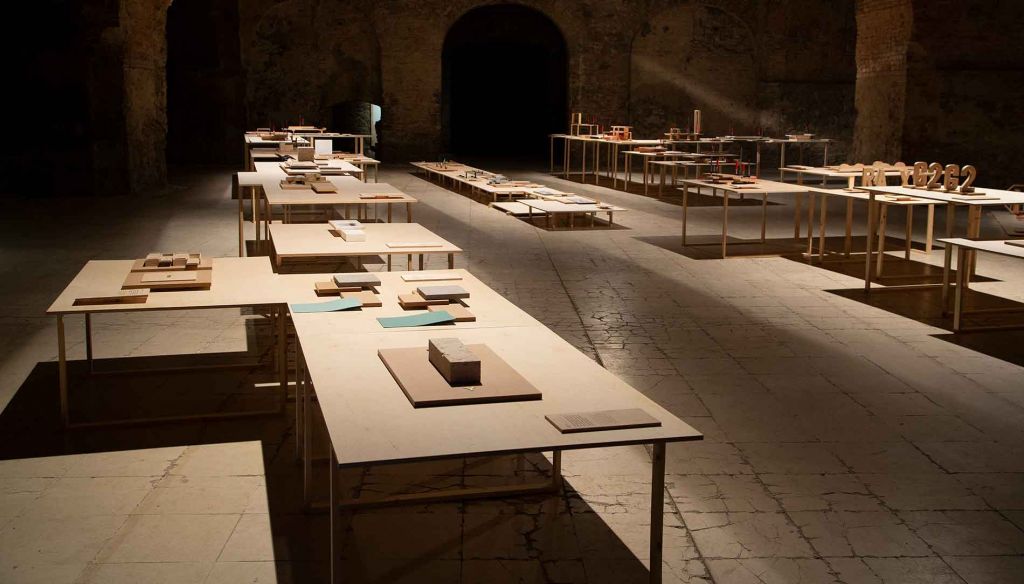

The exhibition has 45 memory models, combined texts, and 5 video projections as a large-scale installation. Based on various professional sources, I edited and formulated in my own words the findings of memory research that interested me the most, writes Asztalos. This dark nave of the ruins of a Baroque monastery church becomes a theater of the mind, a laboratory for memory construction. Wood frames are placed side by side, forming the legs of tables arranged at varying heights, from a piece of wood balanced on wood wedges at floor level to the frames as legs at an average table height.

These varying levels indicate stages in development, in memory production from childhood to adulthood through our association of play and production according to our bodies and their sizes.

The model besides it, number 14, includes two prefabricated iconic trees simplified to elongated triangles with stems. They rest as chess pieces parallel to one another on a rectangular piece of brown Masonite board. The text reads Flexible access to stored information is a great asset of human memory. The key to this is abstraction. The ability of abstraction enables us to grasp the essential aspects of complex events.

These words by Asztalos are a clue to his references to abstraction and its importance in art history. He explains how this exhibition has been predicated on the idea, Many artists have dealt with and are still dealing with memory. This has been a topical issue throughout art history. If you will let me, I would not highlight specific artists but rather talk about using the abstract formal language of the beginning of the 20th century as a visual language. I was interested in how I could use a fine art language from 100 years ago to the present.

This abstract language reminds one of El Lissitzky or even further back to scientific models of our solar system or gyroscopes. These works evoke memory as an act, a placing of parts together, rediscovering elements as a periodic table of signs and events.

The large ‘nave’ holds all 45 models, while the entryway marks a pathway with shelves and projections. Asztalos describes this; There are 5 video screenings at the entrance of the exhibition. I asked 5 people to remember their lives from childhood to the present. I asked them not to talk about it in words, to think inside them. These are static videos, but the individuals’ internal experiences are as moving stories. These videos are screened onto boards set on storage shelves. It’s kind of like we’re in a warehouse.

These large video projections at the entrance become portraits, memories themselves, frames within frames. They are projected onto boards that are not always the same size as the image. The extra space alongside the protagonists, a band of white, suggests an unpredictable element, a casual association of one portrait to another, one overlapping the space of another.

I associate this element of imperfection with one of the texts in the interior of the nave, which is written next to model 8; in our brain, there are no designated memory spaces that serve to store memories in a given format. Occasionally, we connect certain memory fragments to create a memory. The secret to our memories’ survival is that we recreate them all over again every once in a while.

These video portraits demonstrate a classical familiarity from the remote and not-so-remote areas of our collective canon of art history. We know these portrait sitters; they are luminous figures, reminiscent of Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Seated Woman with Her Hands Clasped, Old Woman in a Chair, or The Apostle Simon [1].

They are in ¾ view, unaware of our regard, looking inward, an eternal introspection recorded for history in their thoughts. Asztalos masterfully engages us in this 17th-century regard, translating the medium of painting into a contemporary language of video. The glowing light emanating from the Rembrandt portraits is almost a prediction of how screens and projections might one day represent the internal act of reflective memory. With these works, the artist cements himself in history, a cog in the wheel of time, progressing and demonstrating centuries of memory construction and re-enactment through art.

He remarks that we can not learn the hidden stories buried in the soul of these people. Through this work, he reveals himself, his tender regard for humanity, the unique suffering and solace of a life process from birth to death, and the internal collusion with body and soul at its centre.

I asked Asztalos what surprised him the most in his research on memory. It was very exciting for me to realize that individual and collective memory is based on the same patterns. In essence, there is no difference in how they work. In the memory of a society, the same processes occur as in the individual person. The other interesting thing is that the same processes occur in the memories that are experienced and full of emotions as they have been for thousands of years. Although each person is unique, there is still some general driving force between us, regardless of space and time.

Here, Asztalos taps into the connecting thread of our human civilization, the memory process as both an act and a construction, a shared composition of time, society, and individuals. I think we’ve always adapted our present to the past. We either confronted it or wanted to approach it. The point is that it has always been a point of reference, and in that sense, the time has always been an important consideration, says Asztalos.

I think back over the past year about how I followed the progression of these works by Asztalos in visiting his studio and through our conversations about these topics. I consider how the elements of my own memory have gradually been replaced, reconfigured, and reassigned status and position according to new knowledge and understanding. I nod my head, silently confirming his statement for myself as I read his replies to my questions.

Remembering is really our present state in the light of the past. The real events that took place are a kind of inspiration to write a standalone version of them that only partially fits the original story. Memories are about us on the one hand and the events that have taken place on the other. Which events we select, how to make memories out of them, how to write them down, and how to edit them from time to time, they are always about our current state, our current world. Elsewhere, memory is also related to our vision, he explains.

Asztalos reminds me that with memory, there are other factors of importance. Forgetting is an important part of the process of remembering. Forgetting helps to construct memories. It’s like an eraser for an artist. A graphic artist draws with a pencil and sometimes erases to create his image. I think that collective and personal forgetfulness interact back and forth and are shaped by similar processes.

A social system can shape an individual’s memory, but it can also be true backwards. That is, great historical eras can push the individual’s memory into oblivion, but the individual can also affect the memory of the masses at any time.

His words recall Socrates and Sappho in my mind. These thinkers’ unique contributions appear as reverberations in contemporary culture. Socrates’ thoughts and words passed on through his students, and Sappho’s fragments infiltrated as platitudes and idioms, whose sources we have all but forgotten.

The term amnesia has some negative connotations, but it can sometimes be an important and healthy element of memory. Fading out parts of the past, even temporarily, can also be a protective reaction to our survival, as our memories can heal and make us sick, says Asztalos, poignantly. He has arrived at the heart of the tender balance between the suppression of personal and collective trauma and its remembrance.

I suddenly remember walking with him past the Ministry of Agriculture in Budapest, where he pointed out the bullet holes on its walls, a memorial to the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. I reflect on our exchange about what it was like to live in Hungary up until 1989, when it transitioned from a Soviet to a democratic regime.

He explained that it was not so strict in Hungary as in other places, and then he paused. I imagine his internal reflections at that moment, a flood of memory much like in these video portraits, his Remembrance series 1-5; then, a contemporary platitude comes to mind, birthed from the celebrity artist Marina Abramovic, the artist is present. Asztalos is not often talkative, but he is eternally present in his gaze and his reconnecting, reconstruction, and acts of memory production, along with his own active forgetting, which is unknown to us.

As an artist who has spent several years researching the past and the path society constructs through a canon of knowledge as a combined memory system, this work is a natural consequence to his ongoing research.

Asztalos concludes his thoughts, We also always write the future from the experiences of the past according to our current state. So, our vision cannot be separated from our memory either.