Text by Charlotte Kent

This summer, I saw works of tangled bodies everywhere. There is a craving for skin contact as well as anxiety about proximity in this pandemic moment. Summer is so often a period of revelling in and revealing skin. After a year of quarantines, the physical sought to be palpable and yet, and yet, new COVID variants urged restraint. All the more intriguing then to see not just bodies but merging and melding bodies across art. It was a visual expression of this moment, though one that has always spoken to an age of virus.

I first noticed it as summer whispered its promises in Martina Menegon’s multiple bumping bodies in It’s a Matter of Perspective (2021) for the May exhibit at Feral File, The Bardo: Unpacking the Real. She used her own form so it was herself colliding with herself…apt given the last year.

On July 6, the dancer and choreographer Zoi Tatopoulos posted her most recent work, We Will Find It, on Instagram. The dancers move like insects, zombies, low poly 3D human models. They are distressing, but arresting. The near-nudity of flesh-toned leotards channel human empathy, counteracted by the dancers’ double-jointed scuttling, jerky yet smooth, recognisable yet utterly alien gait. It’s compelling. Within two days, the video had a million views and counting.

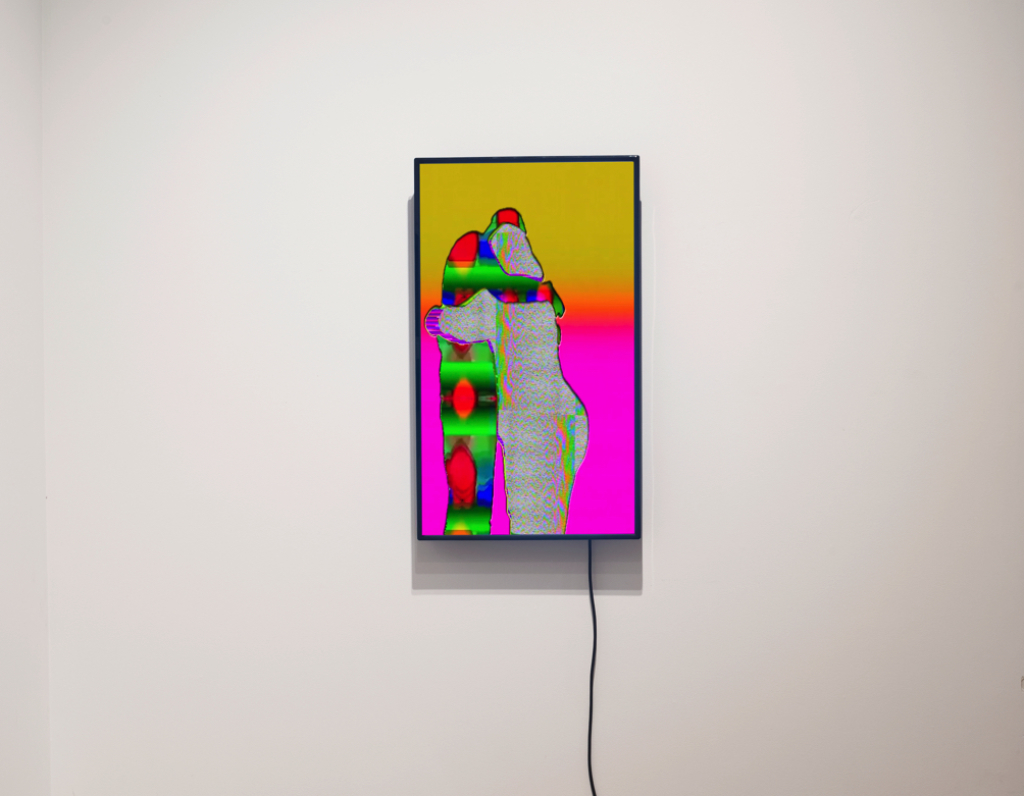

But it was walking into the summer show at Postmasters Gallery, Transfiguration: Leaving Reality Behind, where I started to connect all these bodies colliding. LoVid’s Hugs on Tape (Tanya/Papa) (2021) is a cheerful acknowledgement of the need to touch across the many screens that have connected us for the last year and a half. Using a personally designed audio-visual synthesiser, LoVid presents pools of RGB colour flowing across one figure, while the other form is reminiscent of fuzzy static on a colour tv. They mine the different video signal elements to find those naturally occurring rarities, as they explained when chatting, those glittering moments in technology and sync failure. There is a lesson here for us in what it means to meet again.

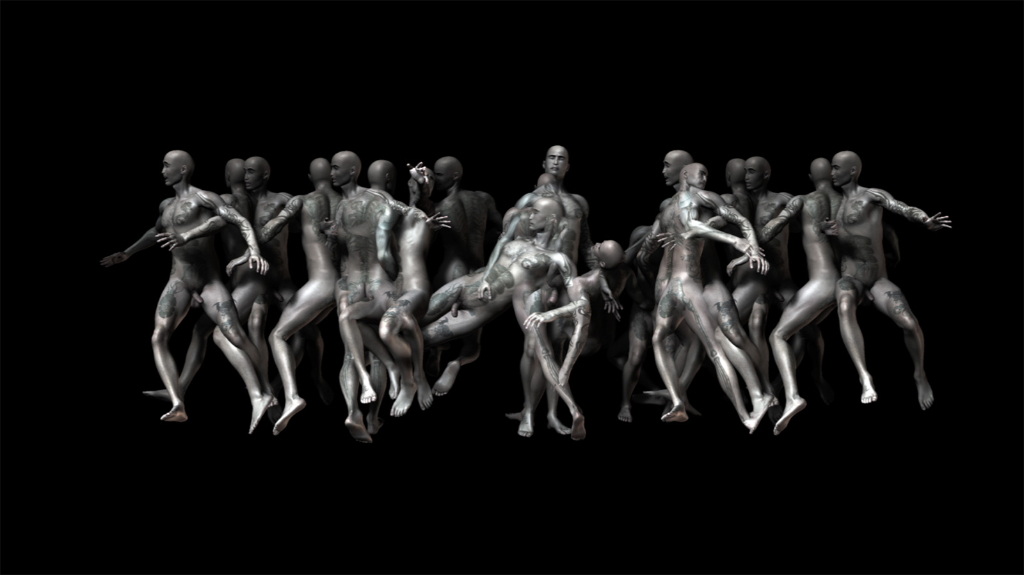

José Carlos Casado newbody.v1e.revised (2004) is one of the earliest works in this spirit, a 3D animation of low poly figures that he specifies are engaged in an infinite dance where there are no physical boundaries; they do not crash with each other, they literally go inside each other’s bodies. These works present a structure of feeling. That is, they are creations of a sense that slippery figures navigating and negotiating each other is something to explore.

As I started digging as to why this felt familiar, I realised it has been there for a while. Tobias Gremmler, an artist who frequently collaborates with dance and theater productions, and did the visuals for Bjork’s Cornucopia Tour in 2019, used it beautifully for the stage production of her song, Body Memory, which he posted on YouTube July 5. Though the work had long since been done, now was a moment for it to return.

Musing on this with a friend, she reminded me of Kurt Hentschlager’s audiovisual installation, Karma/X (2008). Hentschlager, in contradiction to Casado’s perspective, describes his work as a flock of humanoid figures ceaselessly crashing into one another only to be pulled apart again by massive gravitational forces.

It’s as if we are desperate to represent contact even as we aren’t certain we want to breathe the same air, and do not agree if contact is generous and kind, or invasive and dangerous. These representations speak to a transitional moment for us socially, personally, and for art as well. The rise of the NFT market, which Postmasters has accepted with their new PostmastersBC, has put digital art at the center of the mainstream contemporary art discourse.

The colliding virtual bodies offer some of the uncanny movements that have been a part of modern and contemporary dance for decades. I thought of Pilobilus Dance which uses flesh-toned leotards, kin to the stripped-down aesthetic cultivated in the digital works. The body in motion is what is being shown and revered, and likewise, the creation of the body in motion, in person or virtually—the digital artist’s code manipulations and the computer algorithm act as choreographers.

Great dance takes my breath away because the body transforms. Seeing it on screen or in person provokes that question posed so eloquently by Yeats: How can we know the dancer from the dance? How can something as tangible as a human body gift me a sense of the ephemeral? How does something evanescent offer a celebration of the physical? This is a liminal time when the virtual and tangible collide.

The palpable contact available as some of us emerge from quarantine may be part of the desire to show and see such works. Any sense of isolation is contrasted to these tumbling figures who touch, bump, slide, fall, moving in and out with each other. We can want this kind of intimacy even as we know new virus variants are rampant and that such a sensation must be taken with caution.

Artists working outside of time-based media also represent these fantasies and anxieties. Postmasters’ summer show included examples from Aneta Bartos’ Spider Monkeys series (2011-2014), where bodies merge, though with a creepy erotic overtone that speaks to the transhumanist horror of Human Centipede (2009).

Nicola Verlato’s oil on board and a 3D resin sculpture of intertwined bodies, Cosmogeny #4 and Cosmogeny #5 (both 2020), strongly evoke the imaginary of Dante’s Inferno. He wrote that masterwork amidst the waves of Bubonic plague in the 14th and 15th centuries. His was also an age of virus and massive cultural transformation.

That canonical work extricated apocalyptic scenarios for profound poetry and inspired William Blake and Gustave Doré’s tangled, falling forms; Bouguereau’s figures devouring each other; Rodin’s dense bronze bodies for the Gates of Hell (1880, unfinished); Dali’s 1951 illustrations, so shortly after World War II…There is an iconography of Paradise Lost in these snarled, suspended figures, expressive for our moment too. In desperate moments we cling to one another.

I can’t help but think of the Raft of the Medusa (1818-9), and so many others. In plagues of any kind, we are stripped bare. Low poly models can allude to the uncertain connections in our virtual worlds as much as these tangible realms. One body, wretched and alone, reaches out to another. In this age of virus, artists across media present that impulse.

We are entwined with one another socially, politically, and as we must never again forget, ecologically. COVID-19 made that evident. I am tangled in responsibility with those I rush to hug, those I never meet, and those dancing to a very different tune. Tatopoulous used a song by Emily Glass and Dasychira released in February 2020, We Will Find It. COVID-19 was already making its viral impact, though we had barely any idea to what degree. We still aren’t free of it. These artists show us collisions of bodies that ask us to consider how we are entangled and what we need to find together.