Text by Silvia Pizzocaro

The recurrent arguments of immateriality, with its claims for shapeless functions and for information as raw material, continue occurring in a pervasively tangible world: people are surrounded by a universe of tangible artefacts, where relations among people and between people and their world are mediated by the concrete shape of artefacts and the tangible attributes of materiality. Everything is tangibly made of something: our clothes, the everyday objects we use, our devices, and our personal items. The assumptions of the all-pervading pre-eminence of immateriality are rather paradoxically faced with the dominance of materiality.

The surrounding world is still firmly rooted in the physical substrate of matter, be it natural or artificial. Clearly, technology’s immaterial impact – traditional or innovative – on people’s daily experiences has increased enormously over time. For decades, the impact of technology as informatics, electronics, robotics, bioengineering, advanced material technology, and so forth has been largely interpreted as the agent driving the system of products towards the contraction of its material substrate to be substituted by immaterial processes and services. The claims advocated by policies of sustainability, in turn, have addressed dematerialization as the strategy for sustaining ways by which material product functions may be beneficially converted into immaterial performances.

From the perspective of industrial products – in particular – the claims of dematerialisation have largely implied a progressive emphasis on product performance through its communication and information components, overcoming more traditional perspectives grounded in tangible functionalism. Nevertheless, the empirical and social understanding of matter [1], as well as the tangible, human relationship with the substance of things, remains the main part of the process of constructing the world, where everything is made up of substance: objects, personal belongings, and devices, whether technological or not.

People are surrounded and pervaded by material persistence. Of course, materials have not only physical attributes: they have a social dimension, economic value, and perceptive and sensory qualities. We may like seeing, touching, or feeling materials or utterly dislike them. Sounds and noises produced by material consistency may address our senses and play either the soundtrack of familiar daily routines or the resonance of extraordinary manifestations. Natural materials may have a scent, as is the common experience of fresh wood fragrance. Furthermore, materials are emblems, and stereotypes of preferred performances [2]: steel is unbeatable, cement is fundamental, glass is invisible, and porcelain is sophisticated.

Invoked materiality

It is with the expectation of a world to build upon the foundations of (presumed) intangibility that the contradiction with a remarkable tangibility in its strictest sense has been born. Research and development departments are investing heavily in the world of artificial and natural materials in terms of a wide range of physical, tactile, and visual properties applied to a vast and heterogeneous pool of everyday objects and tools.

The perspectives in scientific research include techniques for manipulating matter at an atomic and molecular level, which is bringing aradical change in the creation of objects with improved tangible properties and uses. These are different from the properties of objects that are linked to the macroscopic traits of natural materials but are equally and solidly bonded to the concrete physical nature of matter. In such a physical universe, we may learn that some materials have a smell and others don’t, that some last thousands of years and others turn yellow and crumble under the light, and that the state of materials and their properties is unstable.

At the same time, the vibrant claims from the approaches of anthropology and ethnography, along with with the humanities and social sciences, demand that both the specific properties of materials themselves and the social relationships activated through their technical use and circulation are taken into full consideration. To understand materiality – and, conversely, the traits of immateriality – both the familiar human dimension of the substance with which things are made and the physical universe of matter must be interlinked.

The sensory relation with matter

The empirical understanding of materials remains of crucial importance. As a matter of fact – as we may literally mean – the claims of immateriality continue to unfurl in a pervasively physical world: men continue being surrounded by a universe made of substance. The invasiveness of physical objects is so high that – like never before – we bear their presence directly on our bodies (with a myriad of mobile and wearable technological devices) and in our bodies (by means of prostheses that replace organs or insufficient/missing bodily functions).

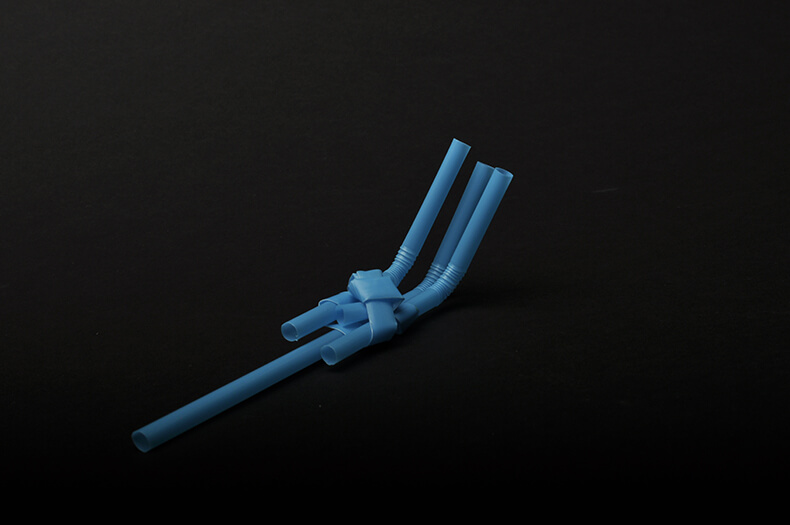

The sensory relationship with the material composition of things remains one of the building blocks of our personal world. Assuming that nowadays, the things surrounding us continue to be, for the most part, tangible, the expression “at hand” may be used to recognize the hand itself – and indirectly the sense of touch – as a driveshaft around which tangibility revolves. The pressure a hand and its fingertips apply to things also tells us the meaning of material manipulation. Touching is a form of knowing: we constantly touch to better understand. Through touch, we recreate a sensory experience of material quality, with its macroscopic characteristics appearing directly liveable and recognizable [3]: contact tells us of warm, cold, soft, flexible, hard, or stiff materials.

Touch or visual information

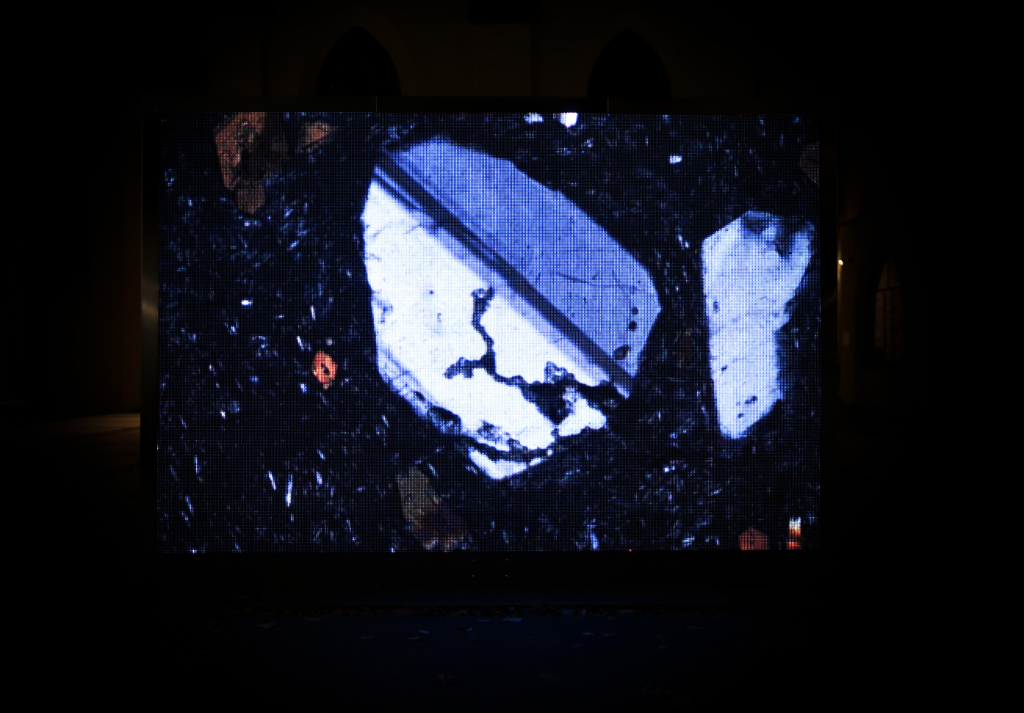

The latter being constantly emphasised to this day – are not the only principles that inform about the nature of matter. Sound, for example, may also express the physical substrate of things, as can be done by smell or – as said – the touch of the hands and fingers. The sounds produced by the properties of materials can affect our senses as much as seeing them.

How materials resound (as opposed to the plethora of sounds and noises artificially generated, as well as phone alerts, off-screen music, and voices produced by invasive artificial sound reproductions) are important in that they express material inner voices: for instance, bronze, glass, and steel produce high-pitched sounds, while rubbers, foams and polymers emit dull, low-frequency ones.

Emphasising the process of the humanisation of matter

The horizon of augmented material-centric options may appear to us as a powerful field of exploration not only for the future – as a constantly updated repertoire of emerging performances and sensory indentities offered by material innovation – but also from the past, in the valuation of material identities modified over time.

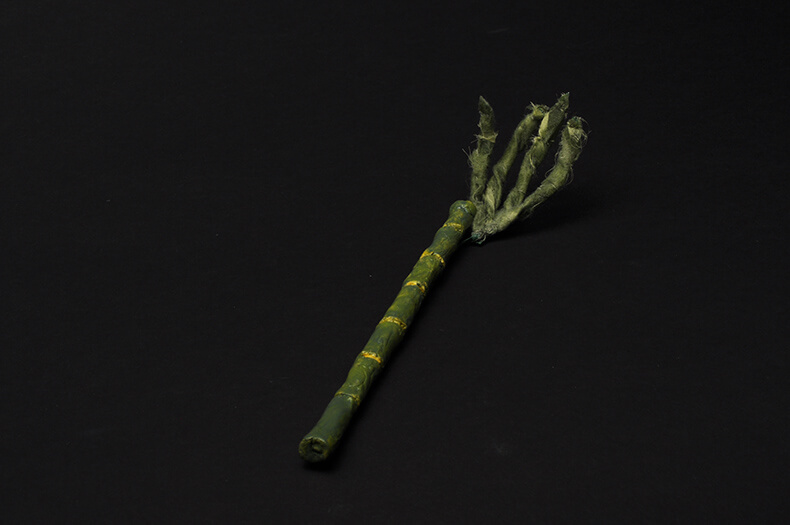

For people, familiarity with the substance of things corresponds to a comforting routine with one’s objects, owned and used with appreciation or – not infrequently – affection. The profound relationship that connects us with everyday objects includes small objects and utensils we could not live without. We would never let go of personal items, belongings, and paraphernalia [4], full of meaning solely for the owner. They are things for which, over time, we learn to acknowledge the shortfalls and defects, including the aging of their composition. Materials, like the objects they form, suffer the effect of time on their surface, which is shown by what is commonly known as a patina, or the trace witnessing that the material has been used.

The quality of used stuff catches the eye with a single look or touch: it manifests reiterated everyday use, a memory of use engraved in the material. The materials that objects are made of may express our behaviour over time and have the ability to suspend or interrupt the uniform unravelling of time itself. The marks of time on materials stop time, and they become anachronistic. But the anachronism and the untimeliness of aged materials may often make them, however, more appreciated: how can one otherwise explain the emotional value and sense of affection exuded by the worn and yellowed pages of a book read over and over or by an old letter, and on the other hand the emotional barrenness of a brand new page?

In contrast with the interpretations that exclusively emphasise the aspiration towards change, and in contrast with the aseptic aesthetics of high-performance materials that lack an identity and social recognisability, we can still report herein the relevance of material permanence and deterioration processes, along with real, concrete, and tangible contexts of materials use, though of course less captivating than the irruption of the extraordinary effects and performances of informed or smart materials.

The current relation with matter is still literally holding on to a tangible sense of materials (either outstandingly innovative or – conversely – traditional, forgotten, anachronistic, consumed, worn), in the context of an individual and collective everyday life that is strongly anchored to a materialized reality.