Text by Jenny Yang & Donatello T. Fletcher

Derived from the Czech word for “hard work” or “slavery”[1], the robot is a powerful concept that allows us to explore themes such as aliveness, agency, labour, and body-mind dualism. With robotics primarily linked to industry, the intersection and cross-pollination between robotics and the arts often goes under-explored. As the world’s first international robotics conference to directly address the importance of artists to robotics research, the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), which took place in Montréal from May 20 t 24, 2019, broke new ground.

What is ‘robotic’ art?

Regarding defining “robotic art, ” roboticist Christian Kroos proposes that the robot makes up the work of art and does not create it, even if they are configured to engage in drawing, painting, or sculpting robotically [2]. Through its interaction with the audience, the robot can explore questions such as aliveness, agency, affect, and even the question of inter-species communication (i.e. how can humans communicate with robots?). These themes were certainly explored in detail at the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) in a series of art installations, which will be outlined below.

Installation: The Obsessive Drafter, by Guillaume Credoz and Nareg Karaoghlanian

The “Obsessive Drafter” is a large robotic arm designed to draw bystanders’ portraits. When interrupted by a bystander, the robotic arm will pause what it is working on, establish eye contact with the bystander, groan, and then stop the larger mural it is working on to sketch the bystander. The installation can form an affective bond with the bystander by undertaking a cultural activity such as drawing. Despite its industrial non-human appearance, the robot’s human-like movement can evoke a sense of compassion in the museum visitor or bystander. The museum visitor becomes both the model for the robotic portrait and the beholder of the art. Using robotics, the installation also renders unfamiliar human activities, such as sketching a portrait.

Right: Mega Hysterical Machine, Bill Vorn. Photo credit: Donatello T. Fletcher. Model: Jenny Yang

Installation: Mega Hysterical Machine, by Bill Vorn

The Mega Hysterical Machine is a spider-like contraption suspended from the ceiling, equipped with a sensing system, a motor system, and a central control system. The installation can detect nearby viewers and will react differently depending on the stimuli its sensors receive. The uncanny movements of the machine signal awareness, engendering questions on aliveness and agency. The installation also touches on modern anxieties concerning machines, automation, and liminal creatures that exist between human, animal, and machine.

Installation: Sound Settler, by Jean-Pierre Gauthier

The “Sound Settler” is an installation that speculates on the possibility of deploying music to “colonize” Mars before the arrival of the first humans. Through interacting with the installation, the bystander can generate interactive electronic music and a 3D simulation of this performance on Mars is generated on a screen. This installation explores the role of the artist in a future Martian colony.

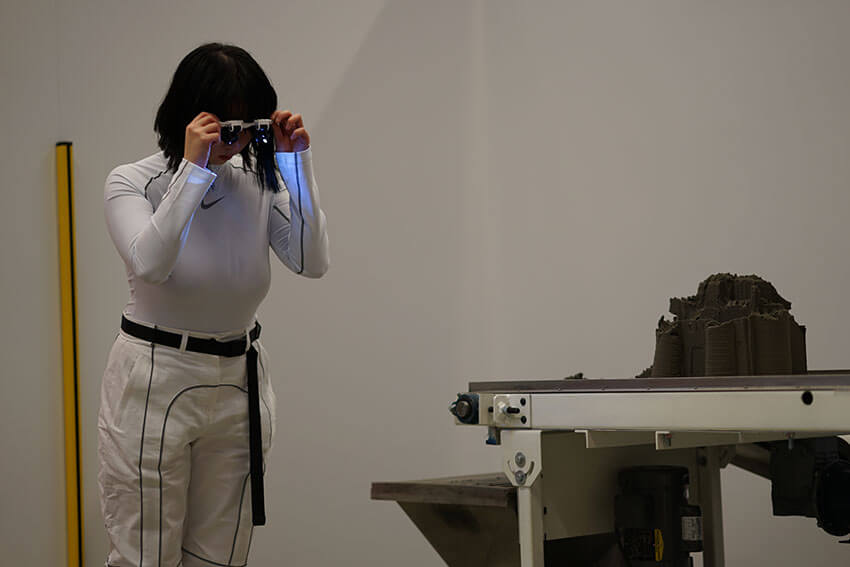

Right: IEEE (2019). Photo credit: Donatello T. Fletcher. Model: Jenny Yang

Installation: Castles Made of Sand, by Michel de Broin

The installation “Castles Made of Sand” is a production line that creates sandcastles, sending them along a conveyor belt. When a “tide clock” set to the tides’ movement rings, the conveyor belt destroys the sandcastle, and the cycle starts over [3]. Watching the poetic “rise and fall of castles” on a conveyor belt invites us to reflect on the cyclical nature of systems, whether they be natural, biological, economic, or social.

Can Creativity be Outsourced to Machines?

At the Paris Biennale in 1959, in response to Jean Tinguely’s drawing machines, many painters of the time interpreted the automation of the artistic process as a “deliberate provocation” and critique of the artist’s role [4]. On the other hand, theorist Leonel Moura believes that if we adopt a less human-focused approach, machines perform actions that are not programmed and are capable of performing tasks that result from an internal information-gathering mechanism [5]. Is art simply the act of capturing content and then arranging and then presenting this content in novel ways? In the future, will we eventually come to recognize “artificial creativity”, the art created by machines?