Intro words by Ana Prendes & interview by Meritxell Rosell

The extraordinarily complex and layered intersection between art, science, and technology has moved from the margins to become a well‐established and institutionalised approach. Curator, artist and theorist Peter Weibel has been long on this convergence, ahead of his time, radically questioning conventional notions of art for over 50 years.

Weibel’s oeuvre conceives artistic creativity as an open field of action. Based on his engagement with language theory, mathematics, and philosophical logic, Weibel developed an artistic language that spanned from visual poetry and experimental literature to performance and the deconstruction of cinematic representation, continually introducing perturbations in our habitual engagements with culture.

His career began in the 1960s participating in three avant-garde movements: Experimental Poetry, Expanded Cinema, and Viennese Actionism, a term he invented, through provocative performances such as Map of Dogginess (1968) with Valie Export. Export took Weibel for a walk on all fours on a leash through the streets of Vienna; Weibel recasts art as a form of institutional provocation.

In the 1980s, Weibel began to work with digital media with his first interactive computer installations, in which he explored the relationship between media and the creation of reality. His publication, Studies in Automation Theory, made him one of the few new media artists ready for today’s technology-mediated world.

Throughout his career, Weibel shifted from his avant-garde art to radical curation. Since 1999, Weibel has led the ZKM | Centre for Art and Media in Karlsruhe. Often dubbed the electronic Bauhaus, Weibel has curated uncountable ambitious and visionary exhibitions, seeking out new forms of experimentation and transformative audience engagement experiences.

His first exhibition, net_condition (1999/2000), happened before most art institutions realised the network would define a new epoch. For his 75th birthday in 2020, the exhibition Respektive Peter Weibel showed an overview of his entire oeuvre for the first time.

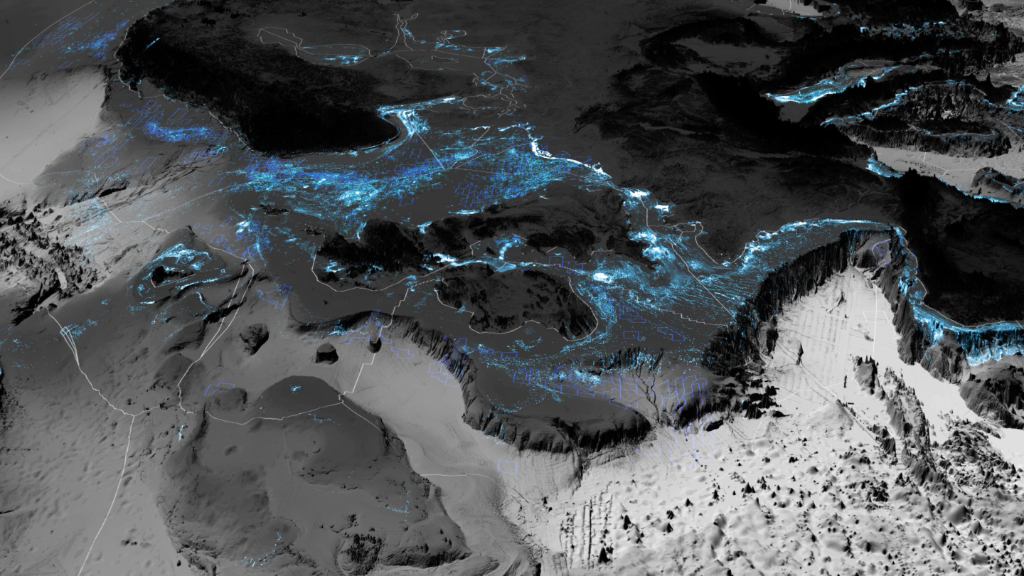

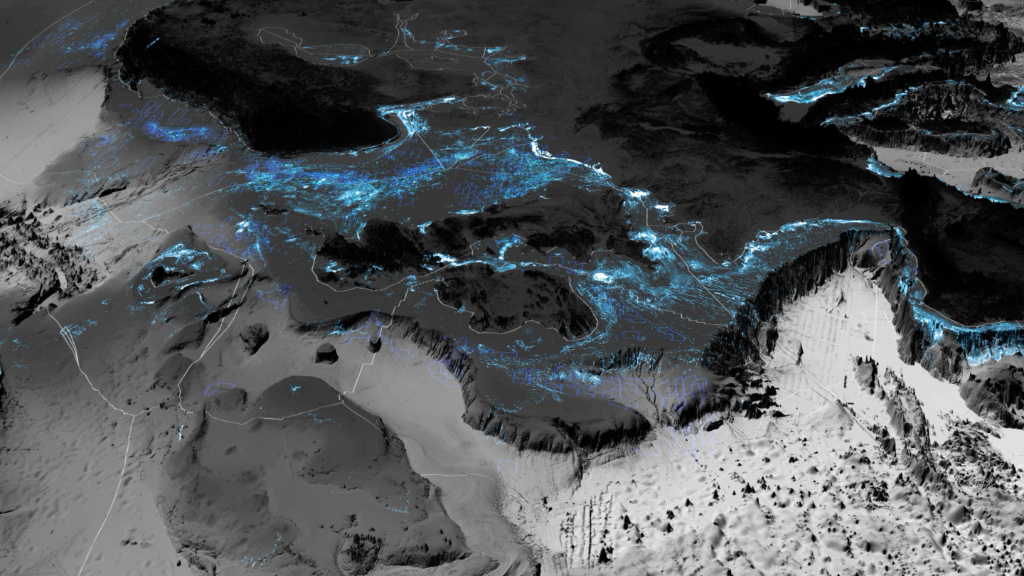

Opening a fictional space to explore the new climate regime, his latest critically acclaimed thought exhibition co-curated with his long-term collaborator Bruno Latour, Critical Zones – Observatories for Earthly Politics, is on view at ZKM until August 2021.

CLOT Magazine spoke with Weibel just before the pandemic hit, but his enlightened thoughts are timeless. His work, from the critique of perception to the critique of language and media to the critique of reality, develops new ontologies that teach us how media constructs the world and how we can construct a new world with media.

Bringing scientific and technological developments onto the arts and back again, Weibel places the artist’s role as an agent of interdisciplinary exchange to explore a landscape of artistic inventiveness, possibilities, and failures.

Your work and expertise are incredibly diverse (conceptual art, performance, experimental film, video art, and computer art); Would you say a central thread runs through and connects them?

What is the central thread to my work? First of all, my art, if my work is art, is interested in cognition. Consequently, it is a critique of all forms of representations, be it words or images: from the critique of perception to the critique of language, from the critique of media to the critique of reality. My work centres on tools that introduce the detection of deceptions and fallacies of media. I do not use photos, film and video to depict the world as beautiful images like painters.

Many media artists are just prisoners of painting. I use the media to show how media constructs the world and how we can construct a new world with media. I am not in the view of the business; I am an ontological operator. First, I extended poetry as a verbal language into new materials, machines, and media into the body, such as language.

Then I operated with these new machines and media to exhibit the intrinsic qualities and how these inherent qualities have been externalised and reprogrammed not only our senses but, above all, the relationship of our organism to our environment.

We can learn from media that our natural organs are just interfaces of the world that realise the world according to their modalities. The final product is a view of the world as a field of variables, except the laws of nature like gravity or E=mc^2. The values of these variables are defined in art by the spectator through participation and interaction, and performance; in them, every human being’s values are defined.

Can you explain how your formative experiences lead to your work in arts, science and cultural organisations?

In my time at grammar school, I have already been interested in the highest abstract disciplines. I wanted to understand the world; I wanted to know. Therefore, I have read the most complex poems, from Luis de Góngora (1561-1627, Spain) to Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898, France) and the most complex theories of physics and mathematics.

My idols were Paul Valéry (1871-1945, France) and James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879, Scotland/United Kingdom). When I was 16, I also read »An Investigation of the Laws of Thought« (1854) by George Boole (1815-1864, United Kingdom/Ireland), even if I did not understand it. But I learned Boolean algebra, which later built the basis for switching algebra.

And I had a comprehensive hunger, which included cinema and music. But whatever I looked at, whatever I listened to, and whatever I read, my focus was always on what these people do and how they do it to impress me, to surprise me, to teach me something.

I did not just consume an Alfred Hitchcock film or a piece by Arnold Schönberg; I always wanted to know how they did it. I was more interested in Edgar Allan Poe’s »The Philosophy of Composition« (1846) than in his poetic work itself. I preferred Vladimir Nabokov’s writings (1899-1977, Russia/Switzerland) about other writers to his novels.

I was an avid reader of Ezra Pound’s »ABC of readings« (1934). In the 60s, I studied all the new sciences, from cybernetics to semiotics, from structuralism to psychoanalysis, and the old science like Marxism and old philosophies like Platonism.

But my main interest was natural science. Coming from a highly low-income family, and being a displaced person, my only problem was that nobody supported me, and I only got what I fought for food, books, education, knowledge, etc.

I was pretty alone in this world and grew up from my sixth year in state institutions and foster families, and therefore suffered a lot of the world’s injustice. And this was the source of my rebellious temperament; consequently, I became a member of revolutionary art movements, like Experimental Poetry, Expanded Cinema and Viennese Actionism (I have coined the term). The vehicle for my insurrections against a repressive society was my art.

You were among the first to write and work at the intersection of art, science and technology. Throughout your career, this recent artistic discipline has moved from the fringes and underground to something more established, and we think, in some instances, even commodified. What is your perspective on this evolution?

Your observation is right. When I made experimental art in the 60s and studied at the same time mathematics and logic, when I was deeply involved in extremes of abstraction like automata studies and extremes of actions in public places not announced as art, everybody said you are wasting your time. The alliance of art, science and technology was for decades marginalised and now moves in the direction of the mainstream.

My perspective is the following: We have to make a difference between the artist and the art institution. Some artists are revolutionary and ahead of their times. But most art institutions and the art system itself are reactionary and backwardly turned.

Most museums today are 100 years delayed. They prefer to show the painters from the 19th century and their modern and post-modern followers repeatedly. I say most museums have the wrong name. They should be called the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Painting; they should not be called the Museum of Modern Art because I do not hear Sound Art, nor do I see many sculptures nor many media works in the museums.

With the event of personal computers in everyday life, even the art world is forced to recognise that we are living not in a painted environment but a mediated environment, that we are living in millions of digital images and digital messages. Even the art world cannot close anymore; its eyes refuse to see the world as a product of science and technology. Therefore I am sure that in 100 years, Museums will celebrate the media artists of today.

Since 1999 you have been the director of the ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, one of the leading institutions working on the crossover of digital, science, art and technology; how do you see the evolution of ZKM through the years? And where would you like to see taking ZKM into?

As the New York Times recently wrote, ZKM is “Ahead of the Curve of Art” (October 15, 2019). When I became director of ZKM in 1999, my first exhibition was called »net_condition« (23.09.1999 – 27.02.2000). Then we made »CTRL [Space]. Rhetorics of Surveillance« (13.10.2001 – 24.02.2002) and »The Algorithmic Revolution« (31.10.2004 – 06.01.2008) or » Making Things Public« (20.03.2005 – 03.10.2005), etc.

Since I am working on the front of research as an artist, I see earlier than others the artists who also work on the front of research, like a good mathematician, know who is the best in his field. We, ZKM, see earlier than others what are the next steps. We have a visionary and, at the same time, critical view on the present and the future and also of the past. Therefore we make shows like »DIA-LOGOS.

Ramon Llull and the ars combinatoria« (17.03.2018 – 06.08.2018) or »Allah’s Automata. Artefacts of the Arab-Islamic Renaissance (800–1200)« (31.10.2015 – 04.09.2016). The 19th century was characterised by the invention of motion machines like railways based on wheels. Motion media marked the 20th century, like moving pictures, cameras, and projectors, which have also been wheel-based.

The 21st century will be characterised by bio-media and technological systems which show life-like behaviour (beyond motion, which was the first simulation of life). Bio-media and artificial intelligence will be a central field of study in the future of ZKM and questions of climate regimes and politics like the transformations of democracy.

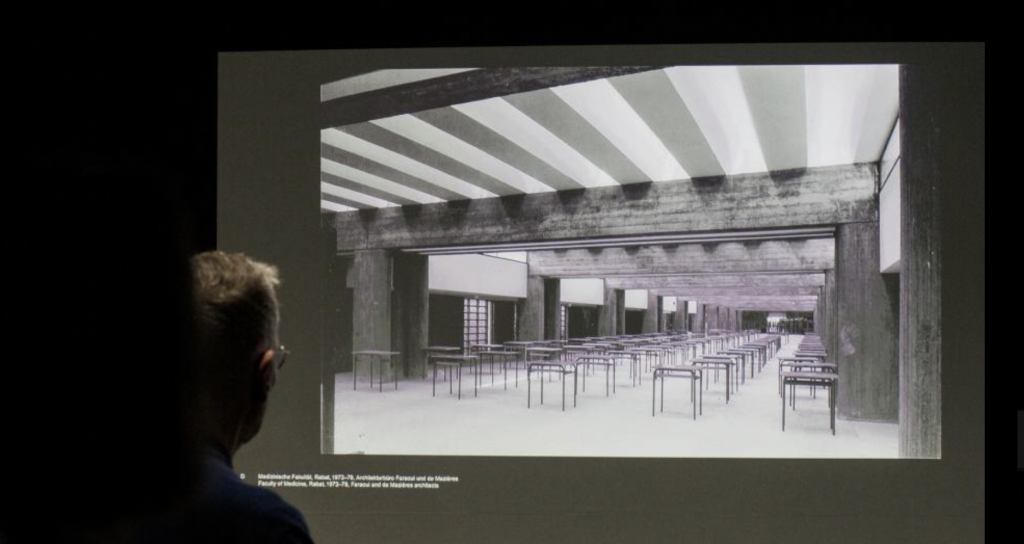

One of the exhibitions we enjoyed at ZKM is The Whole World a Bauhaus; what is, in your opinion, the biggest influence of the Bauhaus movement in its 100 anniversary?

The Bauhaus movement’s biggest influence lies in substituting the word art through design (Gestaltung). Bauhaus was a church of universal design laws (Gestaltung), which can be applied equally to painting, furniture, or architecture.

The Bauhaus books by Mondrian and others have all the word Gestaltung in the title: »New Design« (Piet Mondrian, Bauhaus Book, vol. 5, 1925), »Basic Concepts of New Design Art« (Theo van Doesburg, Bauhaus Book, vol. 6, 1925).

The grid or the counter-position, the primary colours, you can find on the cover of a book; it can form a painting; it can be a basis for a chair (Gerrit Rietveld, »Red and Blue Chair«, ca. 1918) or for a building (Theo van Doesburg, Cornelius van Esteren, »Model for the Maison d’artistes«, 1923).

Bauhaus’s main idea was to discover universal design principles which can be applied to every object, every sculpture, and every painting. You can also see the influence of Bauhaus in the name of Art Institutes. Art schools of the 18th century have been called Academy of Fine Arts or Académie des Beaux-Arts. In 19th-century art, schools have been called the Academy of Art, and the word Fine or Beaux was dropped.

Art schools of the 20th century are called in Germany Hochschule für Gestaltung or America Institute for Design. Gestaltung, Design as a principle, should help make the world more comfortable, more human, and habitable.

I speak about the Bauhaus’s essential value, knowing that there also have been esoteric and spiritual tendencies in the Bauhaus movement, which I neglect for the moment. When I speak about Gestaltung, then I mean the Bauhaus at its best.

When the Bauhaus was closed in Berlin (1933), László Moholy-Nagy moved to Chicago and founded the New Bauhaus (1937), which was later called the School of Design (1939) and Institute of Design (1944). His best pupil György Kepes founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1967.

You see that also here; the word art is dropped. The director after Kepes was Otto Piene, the German ZERO artist who was one of the founding members of the ZKM. A book about CAVS that has been published by the Center and the ZKM has just appeared (»Centerbook«, 2019). Therefore ZKM is truly the successor of the Bauhaus in the age of media. Therefore the ZKM is sometimes called the “Electronic Bauhaus” and me the “Digital Gropius”.

In 2002 you were already talking about surveillance in relation to changing representation and visual arts practice systems. How has your perspective changed almost ten years after, alongside the technologically driven control of surveillance and privacy?

My main thesis was that mass media had trained the masses to enjoy surveillance by creating platforms for exposing privacy, from television shows to social media. They told the people a new version of George Berkely’s philosophy, “esse est percipi” (to be is to be perceived).

This is precisely the doctrine of the actual society: to be is to be observed. When you are not perceived and not observed, it is a signal that you have no value. Today the masses expose themselves freely to be sure that they are seen and, therefore to be sure that they exist.

The old dictum of Descartes, “Cogito ergo sum,” I think therefore I am, is substituted by “I am observed. Therefore I am”, and people enjoy this surveillance of existence. The surveillance has not only become tolerable; the surveillance has become enjoyable.

Privacy has become a consumer commodity to be exposed to market attention. Everybody wants attention, and everybody is ready to pay the necessary price in the economy of attention to sacrifice and expose their privacy.

Privacy has become a globally exchanged value for new kinds of trades and banks. The owners of the platforms for privacy earn enormous profits because their platforms are the stage for privacy exposure. The name of the deal: the more privacy is exposed, the higher the profit.

The meaning of privacy has changed radically. What should be public (res publica) becomes secret, and what should stay private becomes public. The excess of privacy is the basis for surveillance. The sales of privacy and surveillance are the two towers of the Cathedral of demancipation (anti-emancipation).

In times of climate crisis, complicated relationships with technology and political strain, what role does art play today in describing contemporary society?

The role of art in contemporary society has undergone some severe transformations. The dominant role of the art market demonstrates the transformation of art from criticality to complicity.

The former proclaimed autonomy of art has been overturned to the rules of the market and the management. The museum and the gallery are the power triple that is supported by the taste of the collector, which can be manipulated by the museum, the gallery and the mass media.

The result is what Bernard Mandeville has already described critically in his famous text »The Fable of The Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits« (1714). The private tastes of collectors are declared as public benefits. I give an example; in summer 2019, the most powerful gallery in the world, Gagosian Gallery, was participating in the most powerful art fair in the world, Art Basel.

One of the most influential museums of the world, Fondation Beyeler in Basel, showed during the art fair the painter Rudolf Stingel, represented by the Gagosian Gallery and prominently represented in the powerful collection of François Pinault. Here you have not the famous trio infernal but the more dangerous quartet infernal: gallery, fair, museum, and collector.

The other factor why art has lost its autonomy is mass media. The mass media are dominated by a kind of event marketing that praises the worst violations, the meanest and the greatest atrocities. The mass media award the most inhuman, the most catastrophic events with the greatest attention.

Sense is replaced by sensation. Therefore, a show about abstract sculptures in the 20th century has no chance to be reviewed by the daily newspapers, radio, or television because the show is not about human bestiality and not about evil.

But when a theatre announces a reading of Hitler’s »Mein Kampf« and says everybody who enters the building with the Nazi salute has free entrance. This sale of human dignity is awarded evening news on German state television.

This is not fiction what I describe here; really happened in Germany. »The School for Scandal« (1777) is a title of an old play, but only in our contemporary society is it played anytime and anywhere; in that sense, art outcomes to the function of scandal.

Breaking the rules, whatever they are, in the most scandalous ways has become a successful strategy for art. A third factor that changes the role of art is the influence of the ideology of political correctness.

All three factors agree that technological art, media art, and science-based art is of evil. A collector who buys a painting knows that it will easily endure 400 years with some minor restorations. A collector who buys a media work knows its status is precarious and ephemeral: the hardware changes in 20 years, and the software changes in 10 years, so the work is unreliable.

The collector who buys media work also has to buy an engineer who can take care of the artwork’s maintenance. This all affects that today, art is allowed to be everything – political, environmental, moral, ethical etc. – except art. Therefore, the true critique of society is an art, which is entirely media-based, and mirrors and constructs society with the means of contemporary civilisation.

What are your main research interests at the moment? And are there any territories you still would like to explore?

For 1000 years, we have lived and survived with a civilisation based on language and two-dimensional notation (letters, numbers and notes on paper). I am interested in the noetic turn that is a civilisation based on tools. The borders of our world are not the borders of our language; as Wittgenstein said in 1921, our tools stake the borders of our world. With tools, we expand the horizon of the human.

As Stephen Hawking has said: “Nature has said I am dead, Medicine has said I am dead, only Technology has saved me.” For 200-300 years, humankind has created tools and a technology with which man has stepped out of natural evolution.

The Anthropocene is one effect, but not the only one. Fortunately, man has also stepped out from the natural food chain. Animals don’t eat us anymore, but unfortunately, we still eat animals.

With natural resources like oil and gas, we slowly step out from the natural energy chain. We step out from energy resources that were prepared by nature for humankind within millions of years.

Now men have to create their energy sources. And finally, we are stepping out from the natural thought chain. The event and the rise of the so-called thinking machines signify the beginning. Therefore I am interested in the territories of trans-humanism and artificial intelligence. For the year 2020, I prepared an exhibition with Bruno Latour about the new climate politics called »Critical Zone«.

For the year 2021, I will prepare an exhibition about bio-media. In the 19th century, we created motion machines based on wheels, and in the 20th century created motion images, respectively, motion media. The 21st century will deal with bio-media, which demonstrates life-like organic behaviour.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I don’t dare to say it: my body. When I was young, I believed I am immortal. I had three jobs at the same time in one city. I had three professorships at the same time in Vienna, Kassel and Buffalo. But now, with 75, even my body becomes tired and sick from time to time, which puts me really into panic.

I cannot work any more than 72 hours, though, and I don’t want to take pills to keep me awake. Therefore, I hope that my body will be gracious and give me many chances to be creative.

You couldn’t live without…

Art, civilisation, culture, democracy, love, science (in alphabetical order).