Interview by Adriana Ciotau

When we think of Jenny E. Sabin, we think about the background and ambitions that have crossed boundaries in research collaboration. Her extraordinary motivation drove her above and beyond, somewhere between an architect and an inventor.

Jenny E. Sabin developed a strong knowledge of particular materials. For instance, working with clay and ceramics, understanding the numerous constraints that go into working with clay. This experience, along with experience in digital techniques and computational design, led to the development of projects like PolyBrick.

The project PolyBrick represents a way to integrate a ceramic form into the design arts and architecture through design, production, and digital fabrication. Therefore, with the use of algorithm design techniques, the first 3D brick wall was produced from non-standard ceramic brick components.

Added to this, also her interest in interdisciplinary practice led her to collaborate with material scientists, mechanical engineers, and biologists to probe, experiment with and test bio-materials and explore their fabrication potential and performance qualities.

For example, the eSkin project questions how architecture could respond to issues of ecology and sustainability. The result represents an optimized building skin; in that way, the buildings can adapt to changing external environments. In general, research labs are developing, according to their needs, specific design tools.

Also, the labs utilise a mode of research which integrates: information, data, techniques, other tools, and theories from various disciplines to advance fundamental understanding.

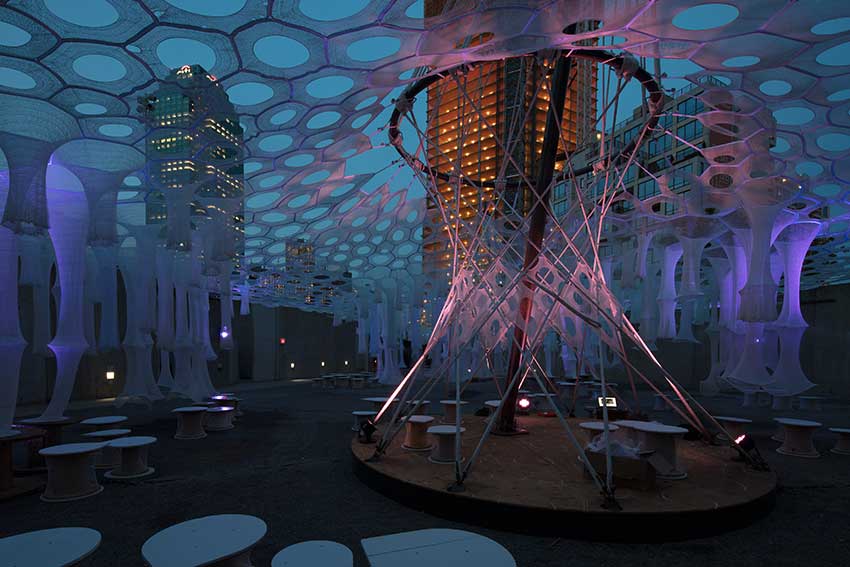

In 2017, Jenny Sabin Lab won the MUSEUM OF MODERN ART‘s PS1 YOUNG ARCHITECTS PROGRAM 2017 with the Lumen Pavilion. This project is a result of Sabin’s preoccupation with designing and generating an ‘organism’ that operates as an environment.

Right: Luster for House of Peroni, a project by Jenny Sabin Studio, curated by Art Production Fund. Photo credit: Chris Eckert

You studied art at the University of Washington, and then years later, you did a Master’s in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. Could you tell us what did you learn during your time in both places?

I have a B.F.A in Ceramics and a BA in Interdisciplinary Visual Arts, and yes, I worked on these degrees at the University of Washington. It was during that time that I developed a foundation in materials and making. Also, a body of knowledge related to clay; The specific working of the material, its chemistry, and everything from glaze calculation to firing techniques.

Even then, I was very interested in the intersections between science, the arts, and technology. I was struggling to find the perfect balance between my interest in science and mathematics with art. Fundamentally, some of the takeaways of that period were developing a strong knowledge of a particular material and the numerous constraints that go into working with clay and ceramics.

I was searching for a creative practice that would integrate mathematics and science with the arts. So, the decision to study architecture naturally came about. Added to this, I wanted to be on the East Coast. I am from Seattle, Washington, which is located on the North West Coast of the States.

I wanted to go to graduate school in a completely different environment. So, I decided to go to the University of Pennsylvania. At that time, the School of Design, formerly known as the Graduate School of Fine Arts, promoted degrees and curricula that integrate art and architecture.

As a student at Penn Design, I was fortunate to experience their transition from analogue teaching of drawing, such as traditional representation methods for constructing plans, sections, elevations, and perspectives, with a move towards digital techniques and computational design.

I spent half of my graduate education learning these fundamental techniques, which resonated with me as a maker coming from the fine arts, and the second half writing algorithms and scripts and learning how to work with digital tools.

The chair of the department at that time, Detlef Mertins, was visionary in terms of the faculty that he hired and the courses that he supported and inspired. It was not just about the digital tools, as he promoted critical discussion around computation and the digital. Looking back, it was a very special and unique time, something that will never be repeated.

In graduate school, I started to understand the fundamental differences between what it means to make art and what it means to make architecture. More specifically, in the context of digital tools, there was a lot of discussion around themes like the emergence and complexity of dynamic systems. As much as I was in it and a part of this culture.

I started to be a bit critical or self-critical of this discourse and thought that maybe we could learn something from our colleagues in the sciences rather than opportunistically borrow these scientific terms. I was invited shortly after I graduated to teach in the graduate program at Penn, and I ended up teaching at the University of Pennsylvania for 6 years.

Could you tell us about the final project that you did at Pennsylvania University?

I studied with Cecil Balmond, who is a very well-known structural engineer. He is a pioneer in the area of forming an algorithm.

My last studio was with him, and the title of the studio was ‘Can Architecture heal?’ so I was interested in looking at the relationships between doctors and patients in a hospital setting and rethinking what those relationships may be, especially in terms of data coming from the human body. So, I was thinking about how patients may be able to have more agency in that.

So, the final project was a set of interventions proposed for a new type of hospital that would facilitate more positive exchanges between doctors and patients and nurses. It was a system, a structure, and an environment.

One materialized artefact (Body Blanket) was woven on a digital Jacquard loom that was generated by a simulation of human-bio-data sets. My interest in data-driven design, interactivity, and linking digital space with materials and textile processes was explored in the studio.

My first encounter with your work was when you won the Young Architects Program in 2017, run by MoMA and MoMA PS1. For me, it was very interesting to see how you designed and generated an organism that operated as an environment as opposed to an object. How did your interest in experimental architecture develop?

I would say it started with the foundation that I experienced in graduate school at Penn, combined with my art background and interest in experimentation across disciplines. Having the opportunity to teach allowed me to develop this further and question my trajectory.

I worked with and met some amazing creative thinkers early on. This interest has been substantially bolstered by my collaborative research and work at Cornell University over the past 7 years. Early on, I was part of a group called the NonLinear Systems Organization.

This organization which included faculty at PennDesign and was started by Cecil Balmond, Detlef Mertins and several participating faculties, engaged in critical discussions between architecture and multiple disciplines across the University and beyond.

During the first conference that we held, we invited people interested in mathematics, the sciences, and architecture. It was during that conference that Dr Peter Lloyd Jones, who is a cell and molecular biologist, wandered into the event while taking a walk across campus.

He saw a sign for the NonLinear Systems Organizations, and he thought:” Wait a minute, I am a nonlinear system biologist, so what are these architects doing?”. He stayed for the full day of the conference proceedings. He introduced himself to me at the end of the day, and we exchanged cards and, from that point, started a multi-year conversation.

That initial discussion led to a year of exchange. We both hoped to generate a common ground for collaboration through clear communication and trust. I attended his weekly lab meetings, and he attended my studio reviews and crit discussions.

I was focused on trying to understand the biological systems that they were researching as a designer and, most importantly, developing strategies for talking and working together collaboratively.

So, over that year, we figured out how to talk with each other. It is hard to collaborate, especially across different disciplines, when you have different structures in place – how we teach, garner funds, publish, conduct research, and even how tostructure your day.

After that year, we started co-teaching a course in the graduate department of architecture at PennDesign called NonLinear Systems Biology-Design. We co-taught the course for four years, with students participating in architecture, bio-medicine, history of science, and materials science.

We also launched a hybrid research and design unit named LabStudio (LabStudio was active till 2011. It started in 2006). To our knowledge, this was the first collaborative research unit between a biologist and an architect. During that time, I could say rigorously my interest in experimental architecture started.

I’ve published a book, LabStudio: Design Research between Architecture and Biology. It is a book documenting the early years of LabStudio and more current work ongoing in my lab at Cornell Architecture. It is a book about collaboration, research methods, computational tools, prototypes, and hybrid work that emerged from that experience.

ou have an elaborate series of projects that engage textiles and embedded data structures. Could you tell us a bit about this experience? Also, about the projects that you have developed regarding the focus on multidisciplinary research and design?

The architectural projects that engage digital textile processes, surface design, data-driven form generation, and responsive material systems made a substantial leap in 2012 through a commission that came to me through Nike and several subsequent projects.

And so, Lumen was the fifth instantiation of that particular material system, so I was confident that it was ready to go outside and operate at a scale that I had never achieved before. The work that I do at my lab, collaborating with scientists, engineers, and so on-mo

st, is fundamental research that is not necessarily focused on application and scalability.

However, it’s in the lab where we can explore material principles, biological systems, and rigorous collaborative exchange. So, I spent eight years deeply researching surface design and multi-cellular structures with Peter through his lab and in the context of LabStudio.

For me, it has never been about simply scaling up what may be a beautiful form in biology into architecture. For me, it’s about the processes and the behaviour that is behind those images and how they impact and inform our thinking through the process of design.

Through the modelling, visualization, and research of these biological systems, we are presented with a series of powerful ecological thinking models where context informs form, structure, and function. I guess you could say that the built projects are analogues of this type of hybrid thinking.

Projects like Lumen and House of Peroni exhibit nonstandard component-based cellular forms, but they are not a mimicking or 1:1 translation of a cellular biological system.

It is a way of thinking that is a result of multiple years of research, experimentation, and material analyses across disciplinary boundaries that inspire and aid our design explorations. The material, geometry, form, context, and human interactions, and all these things can be folded and integrated into the design process, are what fascinates me most.

It comes from a deep analogue understanding of how the form works in nature because those aspects are never separated. From the beginning, in all my projects, the material investigation is deeply embedded. The links are through thinking and forming bridges with collaborators through tools. Testing and iteration, productive failures, are achieved through prototypes and digital fabrication experiments.

How important is prefabricated architecture from an environmental perspective? What is your approach when you choose a material to work with it?

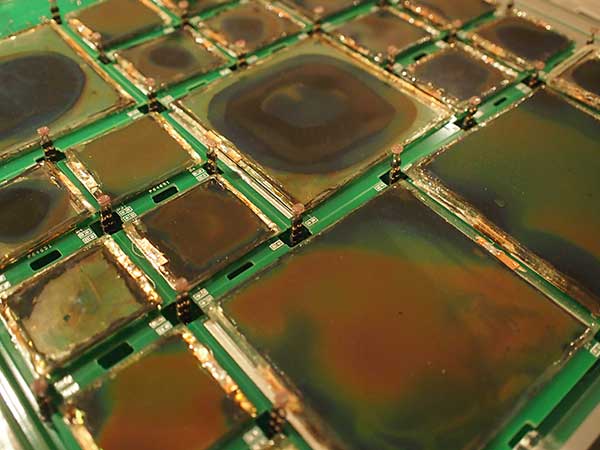

I am very interested in the relationships between beauty and sustainability, aesthetics and sustainability and how it may begin to personalise architecture. So when I select the material, sometimes is influenced by my collaborators. For example, Shu Yang, an early collaborator who is a materials scientist, has done a lot of work on the topic of structural colour. This led to a 4-year collaborative project on responsive materials.

We explored the behaviour of light with nanostructures and materials to generate strategies for adaptive building skins. Structural colour continues to be something that I investigate in many different ways and through multiple materials, including some of the yarns that I work with within the knitted canopy structures.

Structural colour change not only depends on the wavelength of light but also depends on human perception, the geometry and texture of a particular material at the nanoscale, and how together this contributes to programmable materials and responsive materials that dynamically change their colour and transparency.

Other times, we may focus on a particular performance and the related effects and responsivity that I am interested in capturing. A lot of this is driven by our ability to design the responses that these materials can achieve. Simultaneously, I am also interested in choreographing these material performances as part of the design process. Materiality as a spatial concept is something that is co-produced between the responsive material and our engagement.

Your interest in experimental architecture can be traced throughout your professional projects, not only in your multidisciplinary collaborative research but also in your academic career. What do you teach at Cornell University, and how would you describe your experimental teaching methods within architectural education?

I have been teaching now for almost 15 years, and I think the projects and my research–what I do in my lab along with my practice–keeps me going and keeps me excited. However, I think my biggest impact is through my teaching in terms of long-term influence.

First of all, I am an educator, and I love teaching. It is something that influences the work. Fundamentally, I want students to think a bit differently and engage alternative methods in the design process and encourage them to think for themselves to take initiative.

More specifically, I teach design studio, and I lead seminars that explore emerging technologies and digital fabrication at the intersection of architecture and science.

I expose them to a generative design process that is different from what they have engaged in previously, and, in many ways, I think for them, this is the hardest thing, to stretch outside of their comfort zone, not to know exactly what the final form will be. Maybe because they were exposed to a more traditional way of designing in architecture or are not comfortable with letting go of control. As soon they are able to let it go, that is when amazing things start to happen.

Added to this, we are experiencing one of the biggest paradigm shifts in architecture in the context of digital fabrication and the making of buildings.

It is impacting the way we represent information about form and architecture. So, rather than draw a plan or a section, we can write a script to make something with a robot. This allows for a more fluid connection between making, building, fabricating, and constructing. That is where biology and nature can be great teachers!

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

A lack of time. I am trying to do the impossible: Run a lab with a full team and collaborators while simultaneously running a practice with another separate team and clients. Both have separate but integrated models for practice, from deadlines to research and project topics, and so on. And I am also a full-time educator!

You couldn’t live without…

My creative work.