Interview by Allan Gardner

Hans Berg is an artist and musician currently living and working in Berlin. Berg produces an eclectic output ranging from what could be considered more traditionally dance music, with elements of techno, house and electro, through to artistic collaborations with his partner Nathalie Djurberg – often more abstract in nature.

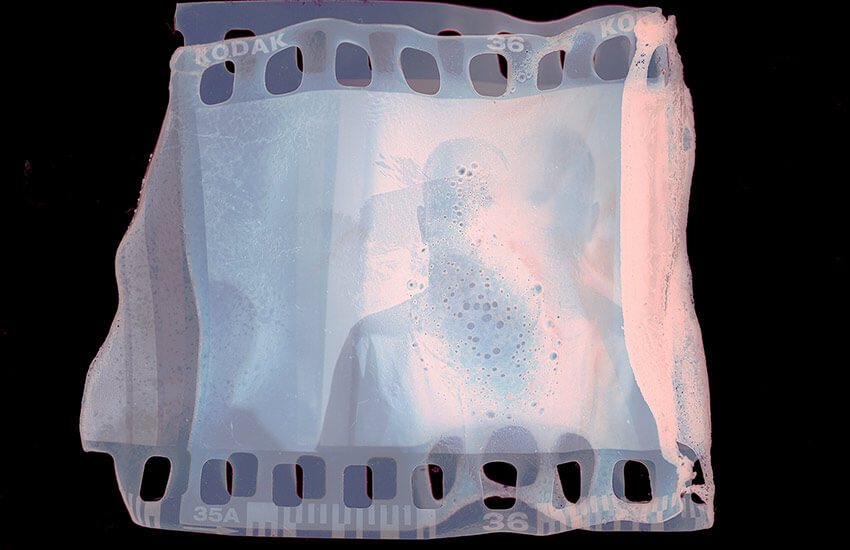

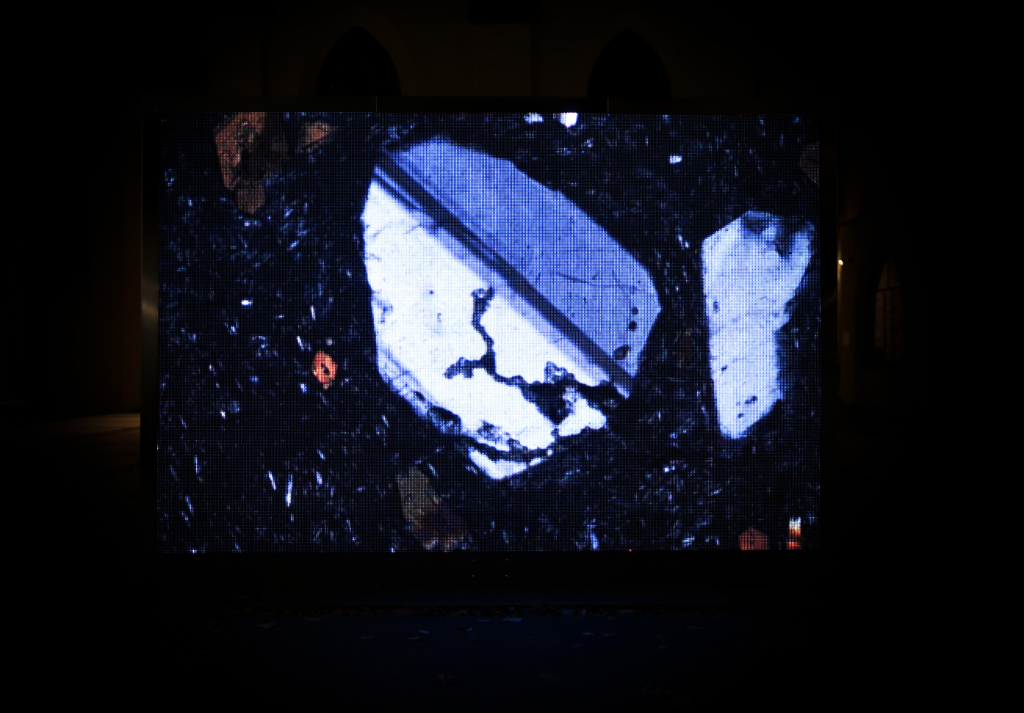

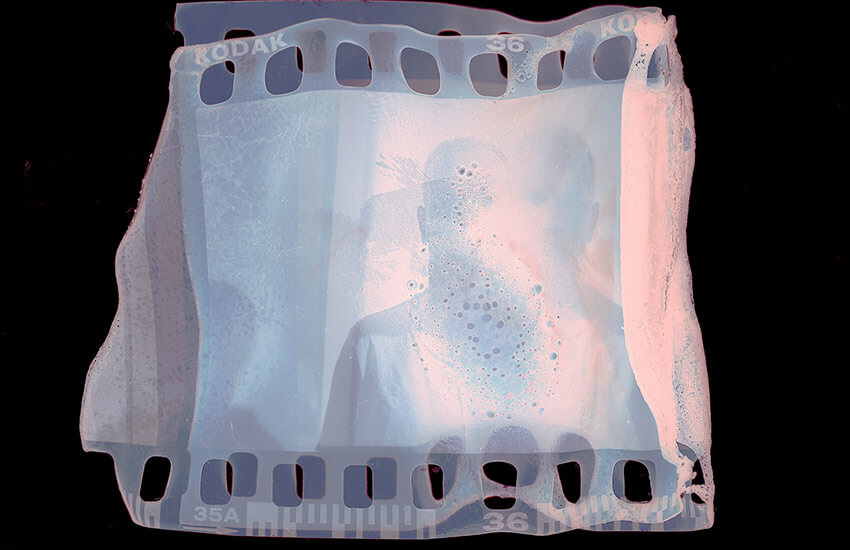

As a collaborative duo, they produce animations built from sculptural creatures made by Djurberg and soundtracked by Berg. His audio contributions to the work range from the collecting and editing of samples production of more traditional musical soundtracks and experimental elements lending themselves more to an abstract kind of foley.

Their collaborative works have been widely exhibited internationally in high-profile galleries like Lisson as well as public institutions, including Stavanger Art Museum, Baltimore Museum of Art, Schirn Kunsthalle and many more.

In 2017, Berj and Djurberg showed a series of works at Museum Frieder Burda alongside paintings and drawings by Willem de Kooning.

Part of this exhibition involved mirroring their output alongside that of the 20th-century master through the installation of audiovisual works in Salon style, as well as displaying the original sculptures used in their animations juxtaposing de Kooning’s paintings.

This decision evokes the discursive aspects present within their collaborative practice, pointing particularly at a reliance on intuitive production alongside freedom of expression.

Berg’s working methodology is inclusive of varied techniques. His audio works are produced using field recordings, hardware synths, modular equipment and digital synths/DAWs, dependent on what is most relevant to the project at hand.

His distinction between organic and inorganic sounds does not emphasise debates around analogue and digital or hardware and software, instead choosing to define organic sounds as those which are self-generating, harbouring their own kinetic energy.

Most recently, Berg has released a new record entitled Sounds of The Forest Forgotten. It aims to conjure musical and conceptual resonances between mysticism and nature. This comes as a reaction to living and working within an urban environment, focusing on the depth and force of nature that is often obscured through the structure of the contemporary human experience.

As well as working within the gallery context, Berg produces club music, allowing this emphasis on experience to feed into his production of artworks and vice versa.

His approach to working with audio is free-form. He appears to be focused deeply on the experience of the viewer and on understanding what will make for the most effective composition in a specific situation.

His myriad of works fluctuate stylistically whilst retaining an aesthetic of mysticism, present consistently throughout his output. Often playful, often humorous, Berg produces with his own voice in the contexts of art, music and the intersection of the two.

Your latest release is also described as follows “Hans Berg’s Sounds of the Forgotten Forest affirms that music can bring us to a state of mind and body that can help us feel what we’ve forgotten from the forest.” How do you incorporate this philosophy into your technique or methodology?

It has to be intuitive, not to be just a craft. I try to follow – or rather feel- the music and not be too technical at the beginning of creating. The intellectual and reflective part for me should come in at a later stage, although, of course, both are necessary.

Your music production stems largely from a mix of hardware and field recordings. Would you describe your relationship with sound design as more intuitive or technical? For example, what does the term “organic sound” mean to you?

Again I would say it’s both. Talking about organic sound is interesting. I think sounds are organic when they move around by themselves, are self-generated, or twist and turn on their own, regardless of if they are created on a modular system or a digital synth in the computer.

Although the sounds on my modular tend to have more life on their own and less control from my side. Then again, there is a much more technical aspect when composing, layering, finishing and polishing the sounds.

As a musician, do believe the experience of art becomes more dynamic when it’s supplemented by audio?

Absolutely, but only when it’s needed. Music can keep you in the space like art cannot. It keeps you contained there, taking away the distinction between what’s inside and what’s outside your body. It tricks you to stay longer than you would have.

It meddles with or steers your emotions, makes you able to connect with feelings in a deeper way than without it, enriches it, and maximises it, but sometimes you don’t want that. You want it clean, not interfering too much, and I love when art that isn’t made by Nathalie and I do that, and I love when it does that in our art.

In an interview with Moderna Museet, you claim film scoring and art music production encouraged you to make music more regularly. You’ve since become a renowned producer on Berlin’s clubbing scene. Have you transposed any of your animation or conceptual scoring to the dancefloor?

The main takeaway for me with this is that I have expanded the borders of my techno music by incorporating the mindset of making the music for the animations and installations. It’s interesting that I’m setting those borders myself and also breaking those borders myself. It’s an internal battle all the time. I don’t observe so much difference in the audience as much as a difference in me that I enjoy music-making more when I expand my ideas and preconceptions of what I think it should sound like.

You collaborate closely with Nathalie Djurberg on her sculptural exhibitions and stop-motion animations, with each of your disciplines working in tandem to create narratives. What format does creative communication between you take, and when it comes to negotiation, what does this entail?

It is impossible to say. We worked for so long together and lived so closely together that what is shared in the creativity is its own entity, sometimes words or mumbo jumbo, sometimes just irritation and gestures and always walking around the subjects because words can seldom express what it really is we’re trying to say. If we could, we would just say it so much faster and easier, but words only get one that far, and they are neither of ours medium.

Solitude or loneliness, how do you spend your time on your own?

I would say loneliness is fear-based. Of course, I feel that it’s existential. In my belief, the only one who isn’t afraid of that just doesn’t know it because they get busy avoiding it. Solitude is profound.

I feel that in nature and in music, either while making music myself or listening to other people, it’s staying with you while not being afraid of being alone, and in music, as in nature, the borders of you can dissolve and when there are no borders and edges defining you, how could you feel alone?

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Fear, all that hinders creativity, is fear. It takes so many forms, the not feeling good enough thoughts, not being brave enough to simplify or maximise, caring what other people think, how someone else did something, and obviously, everyone looks so much better than you. Then, push all that to the background. the second thing is tiredness, not laziness though that’s just another form of fear. Sleep, go back.