Interview by Laura Netz

Christian Duka is a sound artist, both solo and with MARMO (a collaboration with Marco Maldarella), and a techno musician performer in club settings. His experimental sound works are just Immersive participatory body-sound art. Through the use of digital technology, his interdisciplinary art and the electronic dance music he plays do have something in common: they both aim to embody sonic expression.

Duka explores sound art in cross art-forms collaborations involving contemporary dance, performance and visual artists in the context of multisensory, 3D audio-visual environments. Space becomes an instrument at the hand of the artist, a tool at the service of sound & visual design, a canvas where body movements.

Some of his recent works are the series Amoenus, the idea behind creating a spatial sound experience. According to him, the best and preferred one was GUTZ, a blindfolded sonic experience. An hour of sound performance by the sound artists and composers Jose Macabra, Aki Pasoulas, Christian Duka and Guy Harries. The audience blindfolded opened their inner senses to a 58 multichannel sound system.

His latest interdisciplinary piece is UR: Human Presence. A collective and group performance with the use of strobe lights and sound compositions with female voices. The whole experiment has elements from dance, theatre, light art, music and sound art, as well as performance and body art. UR consist of two sound artists, four contemporary dancers, a performance artist, a visual artist, and 30 witnessing participants who come together to portray the inner workings of the human body.

Here Christian Duka, in charge of concept, direction and sound design, has worked collaboratively with sound designer Jose Macabra, performer Elissavet Sfyri – “Nociception”, choreographer Rebecca Evans [Pell Ensemble], and the dancers Ingvild Marstein Olsen, Jasmine Chiu, Antony Daly Luna and Ripp Greatbatch. The graphic design, lighting and visuals are by Marco Maldarella.

He is currently writing a Routledge book on sound-driven, participatory and interdisciplinary artistic experiences that use space as an instrument. He explores the affective power and psychological implications of sound-driven interdisciplinary artistic experiences, and the absence of boundaries separating audiences from performers.

For the audience not that familiar with your work, you are a sound designer, artist and multidisciplinary art curator. What are your main aims behind your practice, which revolves between art, technology And new performative environments?

The main aim behind my practice is to create spaces where audiences are empowered to co-create sound-driven artistic experiences through the use of their body. I am interested in the absence of divides between “artists” and “audiences”, as I believe everyone has an innate ability to express her/himself.

Immersive participatory body-sound art (I just made this term up to synthesise it) enables people to express themselves as artists do – this leads to important processes such as emotional processing and regulation. That’s something that we do when we dream (since we are the creators of those experiences), and it’s how we maintain our mental health. In group settings, the act of co-creation and non-verbal communication, done through sound and body movements, promotes a deeper connection with peer participants.

Finally, I believe that having agency over sound in a shared artistic experience makes us aware of the responsibility of our actions in the “real world” – breaking the illusion of passivity and inescapability of the negative conditions of our time.

The combination of art and technology is necessary for experiences of this kind to happen. My main interest lies in the combination of body movement and sound in 3D audio environments. Technologies like computer vision (position tracking, gesture capture etc.) or even simple devices like wearable accelerometers are incredibly useful tools which provide an opportunity to tie movement with sound in such a way that you can engage in artistic expression simply by virtue of moving.

You are just about to release a bunch of new music publications. What can we expect from these?

I am working on a few parallel projects. On one hand, there’s my practice as a sound artist and researcher. On the other my experimental music project, both solo and with MARMO (a long-distance musical collaboration with Marco Maldarella). Finally, I produce and perform techno/dance-oriented electronic music, that as well both solo and with MARMO.

Weirdly enough, having those outputs parallel to each other seems to work well. My experimental practice sometimes becomes too serious and cerebral, leading to some sort of unbearable heaviness – when that happens, playing in a club or making something less “complicated” becomes necessary to avoid insanity. Whenever I reach what I call “beats overload”, in other words, the boredom of hearing repetitive rhythms, it’s the best time to get back on the other practices, most of the time filled with new inspiration.

Hence, the music publications that are coming will be 2 techno eps and 2 experimental music albums with MARMO, a solo experimental music album and a feature film on my latest interdisciplinary piece, “UR: Human Presence”.

You developed a multidisciplinary series of immersive performative events that focuses on the use of Space as an artistic tool. what was the intellectual process behind its inception? And what were the main challenges you faced for its development?

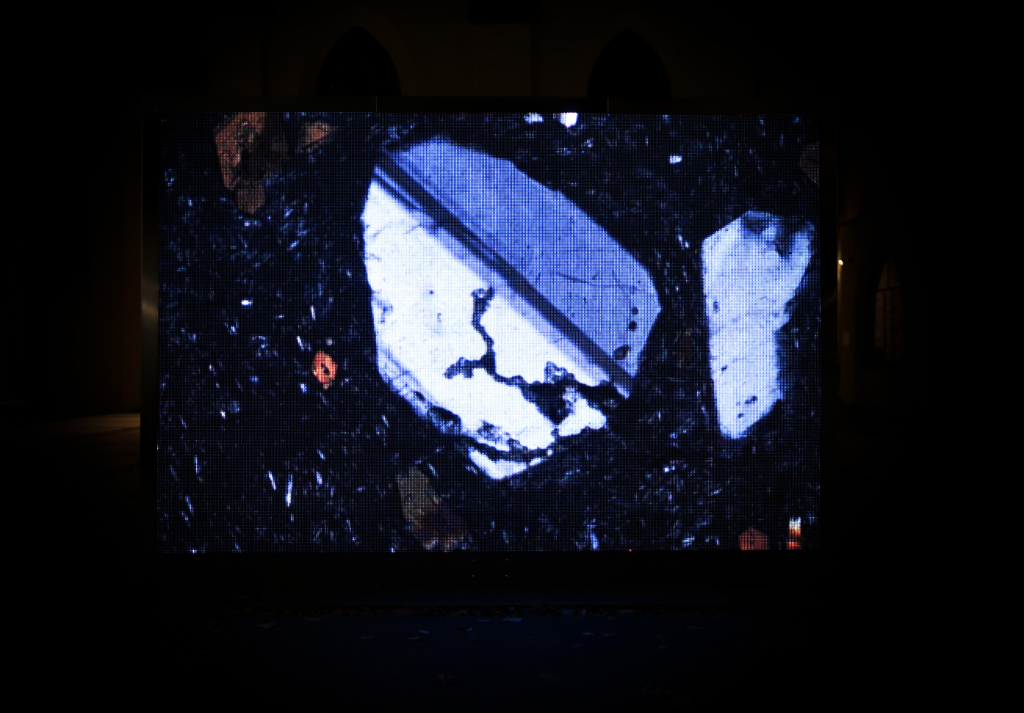

The idea behind Amoenus, the name of the series, was to create a space which felt as though existing outside of space and time, having almost a life of its own. This “feeling” about the Space was created through spatial sound: I have introduced in the venue a software developed by a dear friend of mine, Serafino Di Rosario, in collaboration with Mario Buoninfante, called Auditif – the software allowed sound to be moved inside the space simply by touching and dragging “point sources” on an iPad App. The venue’s sound system was comprised of 58 speakers spread across the edges of the space, meaning that everyone was enveloped by a 3D sound environment at all times.

The idea was to provide the artists with this tool and see how they would use it in their practice for the experience of the audience – in effect, how they would use Space as a sound-design tool. The series had to stop for a series of very unfortunate circumstances – if it continued, we would have tested the use of the Space as a “physical” instrument, using its dimensions for body movement alongside sound (something I’ll do elsewhere next year).

It was fascinating to see how artists used the 3D sound capabilities of the space. Everyone arrived at rehearsals with some pre-conceived ideas of what it would be like and realised that being the Space an actual instrument, they had to change their original plans to make their practice work in and with the space. What was even more fascinating was to see the audience react to sound moving around them – to Space almost having a sonic life of its own.

My favourite event was GUTZ, a blindfolded sonic experience that saw the audience sitting down across the middle of the room, blindfolds on, listening to a 1-hour sound piece created by 4 sound artists (Jose Macabra, Aki Pasoulas, Guy Harries and myself). Some reported feeling the wind blowing on their face, others feeling sound resonating in their teeth, while others mentioned having cinematic/out-of-body experiences.

You are also a lecturer/academic. What are your main research interests at the moment?

I teach electronic music and sound design at SAE Institute and am currently in the proposal stage for my first book, published under the request of Routledge. The book I am writing is on sound-driven, participatory and interdisciplinary artistic experiences that use Space as an instrument (surprise, surprise!).

The research will mainly focus on developing a theory and methodology for the creation of immersive artistic experiences where “audiences” become co-artists, where everyone is empowered for self-expression in a shared space through sound via their body. I am mainly interested in the implications of experiences of this kind in relation to mental health and social bonding.

Your practice is strongly grounded in human experience/sentience and interaction. What is it that most attract you to it?

I guess my practice is a reaction to the default condition of alienation that defines our times, and the ensuing creation of “comfort bubbles” that people tend to create around themselves. We very rarely interact with people that think differently than us – we are constantly fed with the information/points of views we like to hear.

Paired with the self-service tendency of modern-day capitalism and the default condition of “being busy”, it pushes us further apart from each other. As humans and mammals, we have a natural need to bond and get together, physically or otherwise – alienation is a dangerous condition, leading to depression, anxiety and drug addiction in the worst cases.

I guess my practice tries to aid and satisfy that natural need for human connection. What attracts me to it is, I guess, a feeling of love towards other people.

In times when almost everything is consumed via screens and headphones. How do you deal with screen/digital overload?

That’s quite a problem nowadays… everyone today can consume pretty much anything when/wherever they want on their phones, and this takes away the magic of living life through the body. I remember visiting the Louvre years ago and seeing my mother quickly taking pictures of all the paintings on her way, heading to the café and watching them on her phone, sipping her coffee away. This is just a step away from living our day-to-day in VR goggles attached to feeding tubes and a catheter.

It took me a while to get out of compulsive digital consumption, whether on social media or simply engaging in virtual conversations with my friends. More and more, I just prioritise my physical surroundings over the virtual ones. I guess the late obsession with the body in my practice is a reaction to this sad modern condition.

I recently discovered a new type of meditation called “Full Drop”, passed on to me by an amazing choreographer called Margret Guðjónsdóttir. The practice was so much about making a connection with the body that it drastically increased my will to engage with it as much as possible – this considerably reduced the time I spend in virtual life.

The grim vision of my mother watching the Mona Lisa on her iPhone at the Louvre’s cafè is a synthesis of how digital consumption affects art nowadays – many simply don’t see the point in going to concerts or events if they could experience the sound or sight of the same thing at home. In a way, I think this is fair enough – if anything, it pushes artists to create experiences that you simply can’t have in front of a screen with a pair of headphones.

It’s not even about making them immersive – you can do that in VR – it’s all about physical bodies inhabiting a space together, communicating with each other, and sharing an energy that can only be felt in physical reality.

As for my artistic practice, in my late performance piece, UR Human Presence phones were taken from the audience and locked in a box before they entered the space. Many thanked me for that – for how simple this can be, it changes the energy completely in the room – you either stay fully in contact with your surroundings or you get out.

Solitude or loneliness, how do you spend your time on your own?

I love this quote by Robert Fulghum on this matter: “Solitude is not the same as loneliness. Solitude is a solitary boat floating in a sea of possible companions.”

I did mention the issue of alienation earlier, and this penultimate question pushes me to make a point: I believe that not knowing how to spend time with oneself is just as bad as not being able to be with others. Knowing how to be with yourself can actually be the best way of building stronger relationships with others.

I very rarely feel as though I am “alone” in the blue way of thinking about it. I like to say that I simply am with myself, and at the moment, we have a wonderful relationship, probably thanks to introspection and self-listening over the years.

When I am alone, I generally talk loudly to myself – some lone moments through the day can be magical, like the last cigarette/tea before bed, usually accompanied by ambient music and asmr videos mixed on Youtube. As I am writing this, I am spending 2 weeks in Sweden to focus on my book, make music, take long walks in nature and just reflect/internalise the lessons learned this first half of the year – I just came back from a deeply communal experience, Norbergfestival – spending some proper time with myself is exactly what I need right now.

Solitude can turn into loneliness, depending on my inner state. When I am going through hard times, solitude can lead me to feel even worse because of the deep pit of rumination, and that’s when I have to get out of that space and seek human connection – other times, being alone is exactly what I need to feel better, to get to a state where I can be a better person with others.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Fear. And I’ll add: What’s the best friend of creativity? Courage.

Call me lazy, but I don’t have much more to add to that – it’s kind of self-explanatory to me.