Text by CLOT Magazine

As CLOT Magazine announced a month ago, Deconstructing Patterns opened its doors at The Francis Crick Institute in London. The exhibition, which revolves around microscopic patterns, aims to make the research carried out at the Crick more accessible to the general public while engaging it with questions on what art and science collaborations are producing.

We are surrounded by patterns, from nature and form our human creations. Repetitions of structures and shapes. Patterns have fascinated human beings; particularly, artists, musicians, philosophers and scientists, as powerful aesthetic mantras and the core of life itself. Patterns also serve as the basis of epigenetics – or the field of developmental genetics that explains the series of genetic events that end up forming a living organism.

As one of the most fascinating disciplines in biology, the pattern of genes, activating and deactivating, conducting waves of proteins in a magical orchestra. Take the example of the Hox genes, which encode a family of transcriptional regulators that elicit distinct developmental programmes, like body segmentation in fruit flies and extremity formation in mammals, along the longitudinal (head to toe) axis of animals. Hox genes have a restricted expression pattern which, when disrupted, can lead to developmental defects and disease.

Deconstructing patterns has been developed in close collaboration between Crick scientists Iris Salecker (Visual Circuit Assembly laboratory) and Nate Goehring (Polarity and Patterning Networks Laboratory), and three creative artists (visual artist Helen Pynor, poet Sarah Howe and sound artist Chu-Li Shewring), as well as a group of young filmmakers taking part in a project called 1A Arts.

Bryony Benge-Abbot, curator of the exhibition told us that they ‘paired each creative partner with a different group of scientists and provided unique opportunities for them to explore the form and function of specific cellular and molecular patterns studied by their partner labs and each artist was given the brief to develop works of art that would support the visitor journey into the minute world of biological patterns. How often do we think about the intricate patterns that develop inside our own bodies throughout our lifetime?’, asked Benge-Abbot, who is deeply interested in microscopic patterns. ‘

As all scientists at the Crick study patterns in some form, or use pattern-searching as a tool, the theme enables us to present a cross-section of Crick research, offering a glimpse into some of the big questions our scientists are pursuing in the new institute’ she explained.

As a result of this pairing the exhibition is divided into three zones: Infinite Instructions, Transforming Connections and Breaking Symmetry. Infinite Instructions, the first zone, consists of a poetry and soundscape piece by the poet Sarah Howe and sound artist Chu-Li Shewring. Patterns amongst huge genomic data sets are what provide the inspiration for this first immersive installation. Infinite Instructions is a metaphor that describes the way in which scientists scrutinise DNA data sets, going through vast amounts of information as they search for patterns.

It consists of white pods that vary in size and hang from the ceiling. The pods surround your upper body and allow you to listen to various sound pieces. Inside the smaller sound pods, you can hear a poem by Sarah Howe, inspired by DNA and the Advanced Sequencing Facility at The Crick. Inside the bigger pods, four different speakers – symbolising the subunits of DNA: A, C, G, and T – emit sound simultaneously.

Filmmaker, sound artist and sound designer Chu-Li Shewring approached the commission from the scientists’ point of view as a human experience. Shewring told us that ‘one of the recurring thoughts that came up was not just the technological limitations but also the cognitive limitations that we as humans face when we try to imagine, analyse and interpret a [DNA] form so complex.’

so as a sound artist, Chu-Li Shewring can not help asking ‘what is the noise and what is the pattern? Is the noise just noise because there hasn’t yet been a test to see the pattern clearly enough?’

For Shewring, who wanted to take an audience through complicated soundscapes that could easily be labelled as noise, ‘the more I worked with the material the more I enjoyed not only playing with the ideas of noise but also with the architecture and dynamics of DNA and how this could be translated into sound. Working with Sarah Howe was challenging as well ‘[…]

I tried to maintain the rules she applied in the form of her poetry to the movement around the speakers (each of the four speakers representing the four bases A, C, G and T). The form is very apparent when we visually see the poem written down but will the keen listener be able to perceive it through sound? Ultimately it is this idea of interpretation that I enjoy and is so key to the scientists’ work – the more ambiguous elements of the piece should be open to interpretation depending on the listener and their own human experiences.’ Shewring explained.

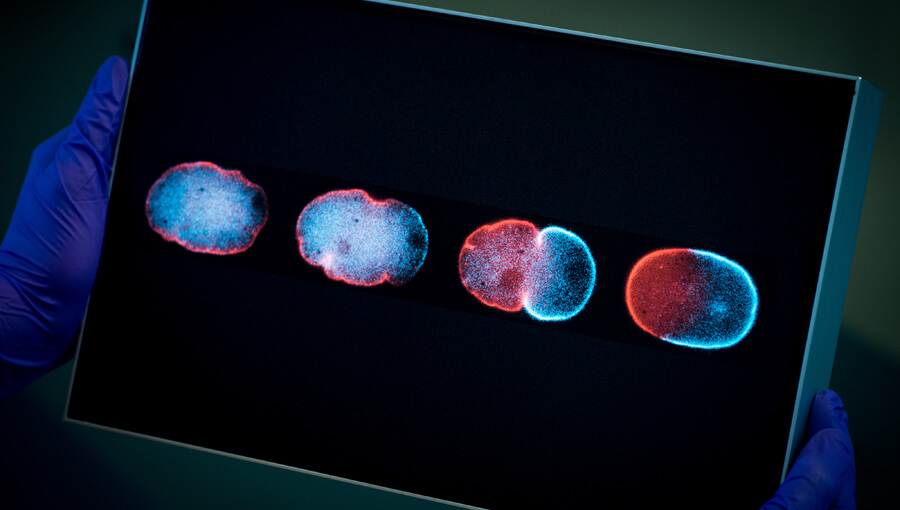

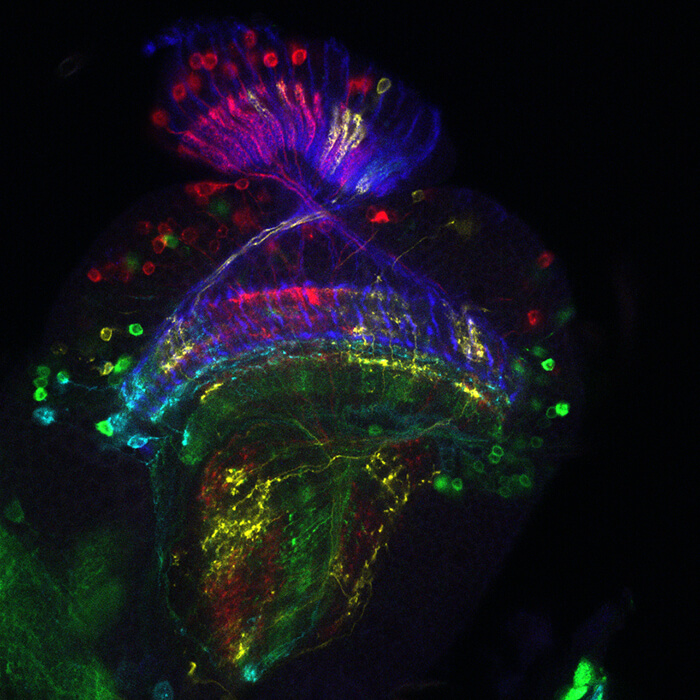

The second zone, Transforming Connections, is based on research involving the development of neurons in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Created by visual artist Helen Pynor in collaboration with scientist Iris Salecker, Transforming Connections consists of a sculpture made from photographs hanging from the ceiling, which displays models of the fruit fly’s optic lobe at different developmental stages.

And as well as a video to show the body language Iris Salecker uses to communicate her work and help to evoke aspects of what is fascinating about the scientific story. This work is inspired by the Visual Circuit Assembly Laboratory at the Crick, which studies neurological conditions stemming from developmental defects.

Helen Pynor told us that, when comparing this project to previous projects in which her interest lied on the transitional zone between life and death, or the transformation of animal to meat, what she found most enthralling was ‘the transformative nature of metamorphosis in the context of the fly eye falls within a broader interest I have in transformative and transitional zones.‘

Adding ‘development takes place through countless intimate acts of recognition and communication. […] biological meaning emerges from the random precision of these many moist moments of molecular dialogue. It’s fascinating, and seems almost improbable, that it all works with such accuracy and predictability.’

There was a long period of engagement with the lab’s research work before Helen Pynor started to create an artistic response. Over the course of Helen’s work with the lab she was ‘gradually developing conceptual and visual responses that took cues from the scientific story and the methodologies being used by the lab, but were also informed by the body language and aesthetic languages that particular individuals in the team employed’, Helen Pynor added.

Part of the artist’s intention in her artistic response was ‘to hint at how scientific practice does not take place in some rarified, abstracted universe where the observers (the scientists) have a disinterested clinical distance from their subject.’

Scientist Iris Salecker is one such scientist and has been obsessed with the ‘architecture of nerve and glial cells in the visual system’ of Drosophila melanogaster (the fruit fly) since her postdoctoral years in Los Angeles. Her contribution to the piece was ‘to introduce Helen Pynor to our microscopic world of brain development studies.’

Iris Salecker and her colleague Emma Powell showed Helen Pynor ‘how to work with fruit flies, how to prepare samples for microscopy and how to capture images using the confocal microscope and to explain more of the background of our research and to convey our current understanding of this part of the fly brain and how nerve cells develop in general.’

One of the challenges they faced was to convey mental images acquired in 2D to 3D, this inspired the film in which we can see how Helen captured Iris’ hand gestures while describing 3D structures.

Iris told us about the positive impact of this collaboration between scientists and artists: ‘We [Iris Salecker and Emma Powell ] were left fascinated when Helen described some of our research as “a sculptural problem”. Developing a better understanding of this aspect – structurally and mechanistically – will certainly remain part of our research efforts in the future.’

Breaking Symmetry is the last station. It is inspired by the research carried out at the Polarity and Patterning Networks Laboratory and consists of a film created by the young filmmaking group KaleiKo. The film is a metaphor for the research carried out by the laboratory and explores the asymmetrical patterns that can be found in the nematode Caenorhabditis Elegans.

Nate Goehring from the Polarity and Networks Laboratory worked alongside young filmmakers 1A Arts to create the short film. Their role in the project was ‘primarily to provide inspiration for the young people, to get them thinking about how animals develop and expose them to some key concepts.

Things like symmetry and asymmetry, the importance of breaking symmetry to generate different types of cells and specifying geometric axes, the need to assign different cell identities, and how simple spatial rules can give rise to complex form, ‘ Nathan Goehring told us.

They developed a roughly half-day workshop to get the young people to think conceptually about how one would go about building an organism. We used iPads and selfie apps to explore the symmetry and asymmetry of our bodies and then used building blocks to explore how the growth and development of animals follow rules – an important idea is that simple sets of rules can generate complex forms. (…) After that, they went off and made the film and we waited to see what they came up with.’ Nathan added.

For him, the biggest challenge was to figure out how to communicate to the young people the scientific concepts in an engaging way. Science is about communicating, sharing and engaging ideas so bringing non-scientists into the lab made Nathan and his team ‘break down our science into its most basic concepts and think about what really defines the essence of our work. And in the process, I think we developed new ways of talking and thinking about the science we do.’

These three examples of collaborations between artists and scientists further highlight the fact that it’ is important that leading scientific institutions like The Crick Institute engage in close conversations with artists.

As curator of Deconstructing Patterns Bryony Benge-Abbot thinks, ‘artists can support researchers engage those who may think that ‘science isn’t for them’, helping to emphasise the relevance, pique interest, raise new questions and encourage dialogue’,. In the last 10 years there has been a steady but increasing paradigm change in the way art and science reflect at each other. A change that started decades ago but keeps crystallizing and giving meaningful reflections in topics that matter in our current times.