Interview by Lula Criado & Meritxell Rosell

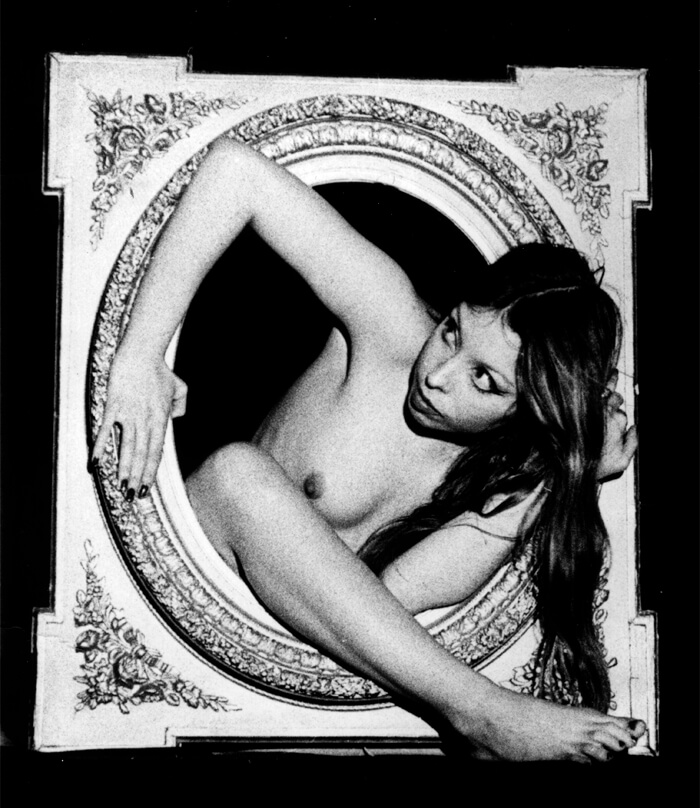

No artists have explored matters concerning beauty and aesthetics of the body so profoundly as ORLAN has. The French performance artist does not need a lot of introduction. One of the most prominent multimedia artists since the 1960s, in the late 1980s, ORLAN embarked on a project involving body modification through plastic surgery. The project lasted only three years, but it sparked an intense debate raising questions about sexuality, technology, gender and beauty.

The main premise of these Surgical Performances surgeries was to transform herself into a digitally designed pastiche of the greatest female beauty icons in Western art and represent the most extreme phase of ORLAN’s artistic practice. Between beauty and horror, the embodiment of ORLAN works recalls to Deleuze’s “body without organs”. ORLAN says she’s beyond any conception of the body “I am both a man and a woman. I feel comfortable in my body because I invented it, built it, and sculpted it to create works of art.” But when you’ve removed the body of its organs, freed from automatic reactions and socio-cultural constraints, then you have its true real freedom.

With Harlekin’s Coat (2008), we see a turn in the artist and her interest in the possibilities of biotechnology. She puzzles us with the idea of the chimaera. In biotechnology, an animal chimaera is a single organism that is composed of two or more different populations of genetically distinct cells (i.e., two different animal species).

Harlequin’s coat portrays the realisation of a patched, organic coat made from an assemblage of pieces of skin of different colours, ages and origins. A prototype of a biotechnological coat consisting of in vitro grown skin cells in coloured diamond-shaped Petri dishes (assembled forming a patchwork design), the piece wanted to symbolise cultural crossbreeding and ownership of biological material.

Regarding tissue and cell culture ORLAN, in an interview with AnOther Magazine (2017), spoke about the impact of discovering the existence of the immortal cell line HeLa1; her perceptions about the status of the living and the dead body, of body material, of what the body is formed, of its function in society and at the same time a tool to carry on experiments that may save people’s life.

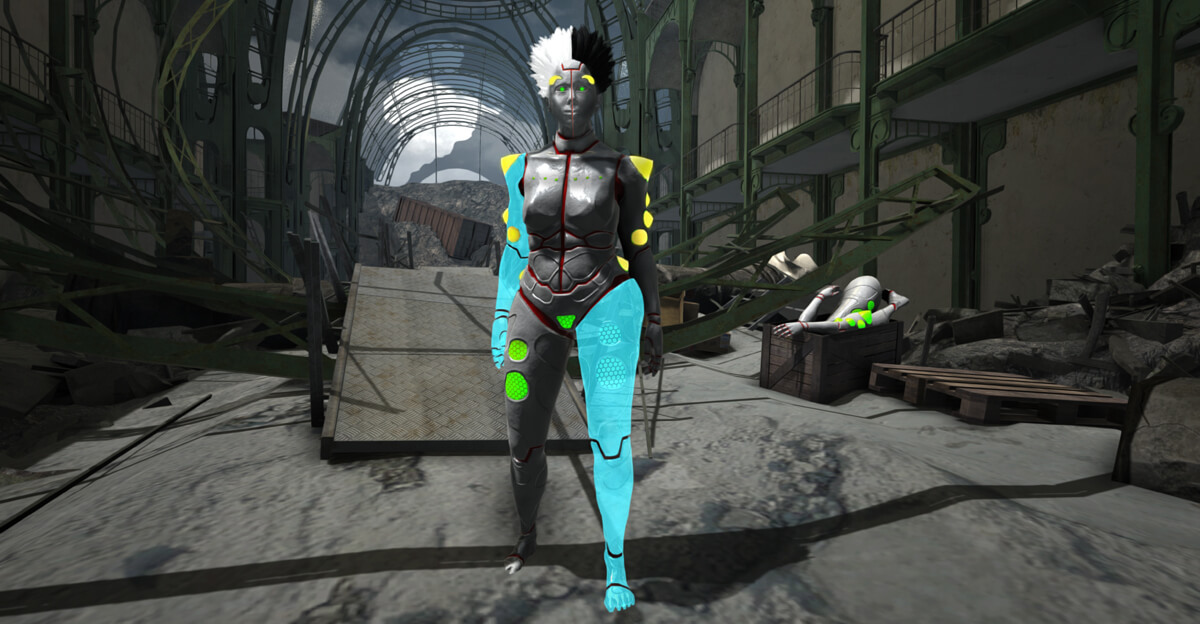

With her immense curiosity, we see how ORLAN has been scrutinising identity perception, and our preconceptions through the different challenges medicine, science, and technology have presented to our societies, such as plastic surgery, Biotechnology and Artificial intelligence. This last one hasn’t gone unnoticed for ORLAN, which has, once again, reinvented itself into the ORLAnoid, a hybrid robot with individual and collective artificial intelligence.

An artificial physical replica of the artist, the robot links different types of AI with a movements generator and a generator of text reads by ORLAN’s voice. The result, as it’s explained, it’s a dramatisation of “deep learning”. The ORLANOÏDE (2018) was created especially for the Art et Robots exhibition in Paris in 2018. The robot is half-constructed. You can see its insides. The sight of the robot and its performance raises issues with individual and collective preconceptions of identity. Through decades of work, ORLAN hasn’t stopped and won’t stop challenging our understanding and interpretation of the self, identity and the biological vessels that carry this identity.

Although your work is not limited to a particular medium, you are best known for your work with plastic surgery (which you only did from 1990 to 1993) and body modification. How do you feel being the artist and, at the same time, the artistic medium?

‘I’ is always someone else. There is always a distance between the two. Sometimes I’m the artist, sometimes the canvas. In my work, I try to portray our world most honestly and realistically as possible. Each time I’ve created a piece of work, it was always to question society’s problems, to say something about the body, as a woman, and as a female artist questioning society about an artist’s place and a female artist’s place in society.

For women, it was more interesting, particularly when I started to work, to reclaim the territory of one’s body and be able to do whatever they liked with it. There was so little freedom for women’s bodies in society because a body is political. Everyone has a body. All my work questions the body’s status in society through the political, religious, cultural and traditional pressures imposed upon it. I’m not interested in the materials but rather in the idea. I try to find the right materials to portray the very essence of the idea.

The operating theatre had to be my studio, and its appearance had to be transformed to become more colourful and humorous. The morbid operating theatre becomes a place for performance and life. Through this artistic practice, the intermediary of the body comes into play, enabling everyone to identify with it, since everyone has a body. This forms a very intense connection with the audience, and it’s this which gives it its character.

You are one of the major figures of body art. In it, the body is used as an open space for dialogue. Could we say that you are exploiting the body’s potential as an artistic medium to modify your perception of identity?

The idea is to blend differences so that we can accept them, to co-exist with the ‘other’ and the ‘I’, which is also someone else, as I mentioned in your previous question. I’ve always called into question the status of the body in society and the political, social and religious pressures embedded in its flesh. I chose to put a face to my face: I’m developing a piece which lies in between figuration and re-figuration. It’s a sfumato between presentation and representation.

I had the idea of including a photo I liked, not due to any surgical necessity, but to reinvent myself. I wanted to give my face an image- a representation. More than an open space for dialogue, my body has become a forum for public debate.

With the term ‘body without organs, ’ Deleuze describes a relationship to one’s literal body as an abstraction of corporeality. What is your relationship to your own body after the body modifications? Have they had any influence on the way you perceive your body?

I am both a man and a woman. I feel comfortable in my body because I invented, built, and sculpted it to create works of art. I’ve always worked with my body, my image and its representation, which I liked a lot, and have never had a problem with. So I did it to bring this image back into question.

It was about using surgery but upending its usual goals of improvement and rejuvenation. The most visible change is the implants which normally enhance cheekbones but which I had put on each side of my forehead, forming two lumps. I worked with the surgeon, asking: what operation can I have that has never been undertaken or requested before, and which is supposedly more ugly or monstrous than beautiful?

If I’m described as a woman with two lumps at her temples, I’m considered ugly and undesirable, but that can change when you see me. Artists today are interested in the context of the body: the body and junk food, pollution, AIDS, the body and new technologies and biotechnologies, the body and genetic modification.

The more that technology is involved, the more we wonder what will become of humans and the body in amongst all of that. My work isn’t a warning about the body. I am, above all, an artist, and it mattered to me to say something radical about the representation of the body, ensuring I become part of history, in this case, art history. Our society is one of three revelatory religions that allow us to represent the body. All our artistic heritage is based on the representation of the body. I am part of the classical tradition of self-portrait, even if my method is radical and uses today’s resources.

The multi-media installation Harlequin Coat (2007) is a prototype of a biotechnological coat consisting of a mix of cells of different colours, ages and origins, a piece that lies at the heart of multiculturalism and the potential of hybridising origins and species. In this installation, you take biotechnology out of the lab, turning it into a spectacle and a follow-up of your previous investigations into hybridisation. What were the biggest challenges you faced in its development?

To create this work, my own cells were extracted and cultivated. I had to have a biopsy which I turned into a performance. Then, this culture of cells was put within a video installation, along with a specially created bioreactor. We put on this play three times, in Australia, in Liverpool and in the Luxembourg Casino. A whole medical team kept the cells alive within the bioreactor during the exhibition.

This time, I harvested my own cells alongside other cells: some of human origin and others of animal origin. Again, it was about hybridisation. During this work, I used the text Laïcité (Secularity) by Michel Serres: I read it during the biopsy.

In it, he talks about the Harlequin as a metaphor for mixing, of hybridisation, because his coat comprises pieces of different materials, colours and origins. Technically, there is no hybridisation but rather a peaceful coexistence of the different elements, a sort of patchwork. Harlequin Coat is, therefore, this video projection where there are videos of large-scale cells living and dying within each square.

New technologies and genetic modification will have an enormous influence on the body’s status in our society and change our ethics, our medicine, and our means and methods of healing. We are currently at a turning point. And we’re definitely not ready, morally or physically, to tackle the problems that will arise.

You’ve recently talked about your fascination with HeLa cells and how they changed your perception of the status of the living and the dead body. New advances in regenerative medicine allow scientists to create lab-engineered tissues and the first versions of lab-grown organs. Would you consider using this type of technique/material for your artistic practice? Are there any new territories you feel you still need to explore or take your work into?

I change constantly and radically that which we take to be given challenging conventions. I’m neither a technophile nor a technophobe. Rather, I’ve always used technology at a critical distance, such as with my work with the Minitel, an internet forerunner. I like to live within today’s reality.

I’m not afraid of technology. I’m more afraid of humans and idiocracy. I like to question technologies in the field of art to upset them, to overturn them, to hybridise them, to shake them to their core. This way, together, we will be prepared to manage these new ways of doing, which require us to think about the world differently.

Today, I’m working on my ORLANOÏDE for the Artistes & Robots (Artists & Robots) exhibition, which will take place in the Grand Palais in April 2018. I thought up this humanoid which resembles me in a hyperrealistic way, speaking with my voice and using my facial expressions.

I decided that this sculpture, this self-portrait which moves and talks and which seems to express emotion, is one of my theoretical and aesthetic representations. It’s, therefore, a robot which will function technically, technologically, and artistically in taking stock, with a critic’s distance, of what robots are today and, above all, what they promise.

They’re interesting and entertaining because we understand that before artificial intelligence comes artificial stupidity, that is, a certain type of intelligence which is vastly inferior to our own. This robot will be hybridised between artificial intelligence and collective intelligence. It produces poetry and text (dancing and singing with my voice).

You define yourself as a neo-feminist, post-feminist and alter-feminist. The Silence Breakers have been named Time magazine’s Person of the Year 2018 because it “unleashed one of the highest-velocity shifts in our culture since the 1960s”. As a witness of the different social (and feminist) movements since the 1960s, what do you think about this cover? Is it a turning point, or have we only scratched the surface?

With the ‘squeal on your pig’ and ‘#metoo’ movements, women suddenly realised again that the word ‘feminism’ was useful and necessary. They looked at statistics on the number of rapes, the number of women dying from domestic abuse and women who put up with being beaten their whole life, or women who have to perform sexual favours just to get or keep a job. We’ve realised that so few things have been fixed and that, again, we needed to use the word feminism.

It’s become acceptable, even fashionable. And men have been using it, too, especially young men. This slogan has the advantage of clearly indicating the aggressor and taking away the blame levelled at women who finally dare to speak out about it, clearly showing that they are not in the wrong. Unfortunately, there are far too many who stay silent.

This start shows that if we accept there’s a problem with the ‘pigs’, we must also accept that there’s a problem with the women who stop other women from speaking out; women with power who use it against other women, for the immense benefit of men; or women working within institutions who stand not with other women, but instead with men, stopping women from breaking the glass ceiling, those who are against parity.

I wrote a text in response to the co-signatories of the petition, which is called ‘Liberté, égalité, sororité’ (Freedom, equality, sisterhood) because it’s the best tool to fight male chauvinism, sexism and rivalry between women, all of which only benefit the masculine world.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Censorship.

You couldn’t live without…

I can’t live without art.