Interview by Piotr Bockowski

‘Mixed reality’ techno-ecologies we live in desperately demand a digital era Gesamtkunstwerk that would encapsulate its problematics in an exciting but non-simplistic way. Most Dismal Swamp is an ultimate collaborative project in the field of media art, which was conceived three years ago by London-based artist Dane Sutherland with exactly that ambition to negotiate novel critical strategies to deal with hypercomplexities of contemporary communications.

Focusing the view on ever-mutating hybrid media meshing online & offline, Most Dismal Swamp experiments with various technologies as it navigates through swampy terrain of ‘amateur heresies’ mediascape in attempts to playfully yet uncompromisingly inhabit such swamps – called by Dane: Multi-User Shared Hallucinations. Constituting our lives, MUSH becomes events involving human actors, Digi models, 3D environs, VR sensors, generated particles and surfaces or synthetic additives merged by computer game engines or other software into on/offline biomes.

In his interview for CLOT, Dane explains sophisticated relations between all those mushy elements, pulling us further into the paradoxical poetics of his post-Internet cultural exploits. Re-inventing the post-modern rhetoric of ‘fluidity’ and ‘liquidity’ of communication ‘flows’, Dane importantly proposes the category of ‘swamp’, which, apart from describing radical enmeshment of media, includes much more than the abovementioned as it also accentuates certain ‘muddy’ thickening as well as blockages of communication in our culture of information overload.

The next event of Most Dismal Swamp is coming on 26 November at the intimate Hackney basement of the Glove that Fits and will witness their first-ever physical release in the form of a nosepiece USB sculpture by Leipzig-based MYEN, who will perform live electronic music with the artificial larynx. Here we have an opportunity to plunge into entirely unique imagination of Dane’s swamp in anticipation of its further embodiments, followed by predictions of creeping “social Balkanisation as communities bonded by institutional mistrust would ferment in private spaces.”

What is your intended conceptual link between swamp and media art? Tell us about your academic background and the origin of Most Dismal Swamp.

I have had an ongoing interest and predilection for all things swampy, slimy, and weird for years without really critically interrogating it to any huge degree. In the early-mid 2010s, I developed some projects that referred more intuitively to swamps – such as the club night I used to run called ‘Daddy’s Got Muscles’ that tried to create the vibe of a virtual swamp in a disused small animal hospital.

As well as a pivotal group exhibition I curated in 2016 called ‘Vaporents’ where I became much more involved as a collaborator (and thus started to move away from the orthodox idea of the curators as an invisible actor). I latched on to what I perceived as the innately heavy ambience of swamps; their characterisation as places that confound the senses and imbue a (potentially fecund) sense of disorientation.

It wasn’t until 2018 that I decided that during my PhD candidacy was a good time to critically reflect and explore these interests concerning contemporary art and the project ideas I have been forming. A year of my PhD was spent not producing any exhibitions or substantial projects – I stuck to the library.

As much as I appreciate the research and theoretical reflection, this resulted in me producing some dreadful work in my thesis. So I ran with my intuitions and extrapolated these nascent concerns, developing an outline for the Most Dismal Swamp project. (My PhD work has obviously been a major commitment in my life, and I find intellectual research exhilarating and enriching, but MDS is by no means an academic project).

After looking into various swamp-related texts, research, projects, artworks, films, music… I rationalised that the ecologies, histories, and lore of swamps could be worked as a conceptual model for understanding our contemporary media landscape and how it is inhabited.

At their core, swamps are neither land nor water but both simultaneously; they are horizonless spaces that impede easy access and restrict progress; they engender a taxonomic heresy that disallows easy separation and parsing of solid forms; they are dynamic biomes inhabited by a dizzying multitude of creatures, including (often marginalised or fugitive) people who have made the swamp their home.

They are historically characterised as evil, dismal, disease-ridden, haunted, and by all sorts of negative connotations by the civil Western imaginary; they are composed of ancient biological strata, and they are fragile spaces that have struggled to retain their vitality as they are slowly eroded by industrial extractivism and frontierism.

Such a conceptual model finds significant traction in a contemporary condition that has now emerged beyond the teleology of modernity and the fragmentation of postmodernity. The non-binary eco-logic of the swamp instead sheds light on an entangled simultaneity of multiple realities and dichotomies that were once distinct and oppositional.

With the ubiquitous and commercial acceleration of CPU and GPU power, CGI and digital compositing techniques, graphics editing software, social media platforms deploying individually-tailored feed-crafting algorithms and data-harvesting, artificial intelligence, and a broad scope of immersive virtual/augmented/mixed reality facilities (procedural compositing of virtual elements and real space using spatialised audio, eye-tracking, retinal projection and real-time spatial meshing).

Things such as reality and fiction or authentic and synthetic or online and offline are ever-more enmeshed. In my initial thinking and communications with potential artistic collaborators for the initial MDS projects (‘Swamp Protocol’ and ‘Whale Fall’), I referred to this as a ‘mixed reality paradigm’.

Swamps then are enacted as a resource for describing platform-mediated realities in a multi-crisis world, for MDS to explore an emerging long-tail of subject positions, navigational protocols, rituals and new forms of community in this mixed reality ecology.

Could you elaborate on your online reference to “Dank Enlightenment” – with possible links to the contemporary philosophy of Cybernetic Culture Research Unit, transhumanism, new materialism or dark enlightenment?

Dank Enlightenment is a term I have playfully deployed to name a way of thinking that is procedurally formed among the systems, artefacts and environmental conditions of this mixed reality paradigm.

Although I have no interest in the reactionary commitments of those that propagate the idea of a so-called ‘dark enlightenment, I have found that Curtis Yarvin’s rhetorical statement, “The other day I was tinkering around in my garage, and I decided to build a new ideology”, to be exemplary of a growing21st-century trend.

This is the inclination towards ‘world-building by way of communal investment in what I call ‘amateur heresies’ – reality models that emerge from para-institutional contexts and the margins of social networks. An emerging long tail of speculative politics that aims to disrupt, re-form and hard-fork the Overton window of viable political discourse.

This distributed heresy is discernible in the growing public distrust and structural suspicion of technocratic regimes and establishment doxa (seen as elite, detached, corrupt and wielding undue authority).

What is now apparent from a glance across our contemporary mediascape is growing social fragmentation and growing investment in diverging alternative ideals, whether this is actionable plans, experimental ideologies, speculative discourses, non-conforming identities, or conspiracy theories.

Each belongs to a bottom-up revision of what is perceived to be the present hegemony (though different tribes perceive different elites; different realities). They are exacerbated by the hardwiring of liberal possessive individualism and tacit online communication protocols into how public discourse plays out across a proprietary mediascape:

militantly aggressive filter bubbles vying to signal-boost their homebaked truths, a kind of cultural arms-race to hypecraft an alternative future doxa by content creators and reality-entrepreneurs seeding a MUSH (Multi-User Shared Hallucination) among a swamp of damned data.

Dank Enlightenment is an acknowledgement of this context collapse of multiple and simultaneous realities and how to actively inhabit such a situation. It is a view from the swamp, from our mixed reality biome. And it is an attempt to self-reflect on this position of being submerged in the vegetal morass of mercenary memetics, the bazaar of amateur heresies, and the dismal banality of algorithmic populism.

What’s your take on the idea of ‘mixed reality? What’s interesting about the artistic juxtaposition between live body performance and computer-generated 3D landscapes?

The actual technology of ‘mixed reality’ itself currently seems more like a languishing vaporware, given the failures of companies like Magic Leap to manifest anything that approaches the expectations their early product promotion instilled.

And the recently staged demonstration of Meta’s (fka Facebook) terminally (and erroneously) monocultural version of the already-moribund idea of a ‘metaverse’ suspiciously excluded all signs of in-app advertising, promoted content, clickbait, and another such slag of the slow crapularity. However, I think this is also one part of the significance of mixed reality systems in terms of delineating a general mixed reality paradigm.

The promissory fictions of mixed reality are, to me, just as definitive of this cultural condition as the impressive array of component technologies already mentioned above (procedural compositing of virtual elements and real space using spatialised audio, eye-tracking, retinal projection and real-time spatial meshing).

Mixed reality systems and their sanguine pitch deck-dreamscapes exemplify and further propagate the already-pervasive form of the ‘composite image’, an elemental and globally definitive component of technological cultures – as actual visual images but also as a way of thinking.

Composite images typically include elements such as human actors/models, digitally sculpted and animated 3D models, sandbox 3D virtual environments, procedural textures and procedurally-generated assets such as dust particles, filmed chroma-key surfaces upon which alternative backgrounds or images are set, and all manner of aggregated synthetic additions or edits realistically merged together by sophisticated (and relatively accessible) software.

I think that these processes are very similar to those that create, reinforce and render in real-time our subjective Umwelten – we each fabricate and inhabit composite dreamworlds or MUSHes in an interconnected render pipeline comprised of tailored media feeds, tribal rhetorics, and the evolutionary selective information processing protocols of own pliant neuroplastics.

Regarding your question about live body performance and computer-generated 3D landscapes, we can see then that the logic of mixed reality/composite imagery is non-binary and synthetic in nature, exposing the fallacy of such dualistic ‘juxtapositions’.

We can think of these things as mixed or composited and by doing so, develop a better understanding of them. For instance, CGI landscapes are things that we build. Therefore they are a part of our extended lexicon of gestures and material culture; they are an extension of our communications, gestures, and actions.

3D landscapes are not ‘places’ or ‘worlds’ to inhabit but material and performative expressions of the ideologies, privileges, and worldviews that condition and motivate us more deeply.

For example, we can find numerous examples of Edenic 3D landscapes that try to foreground slick, fluid and smooth characteristics, reflecting the orthorexic disposition of a transhumanist teleology that presumes a monocultural view of human ‘progress’ and disavows the material impact and substantive contingencies of sociopolitical, geopolitical and technopolitical realities.

Transhumanism operates in a very narrow bandwidth of thinking, conservative metaphysics and epistemic colonialism.

This is another reason I think that the swamp is a valid and useful conceptual model – swamps are, by nature, a thick, tangled morass that is simultaneously fluid and non-fluid, a mixed composite of flows and blockages. The rhetoric of ‘flows’ and ‘fluidity’ that populates all manner of discourses from business operations to contemporary art exemplifies a post-political inclination to veil the cultural and structural restrictions that commonly impede social and economic mobility.

Apart from being a media art (mixed reality) platform, Most Dismal Swamp is also a music label – what kind of sound are you interested in promoting? What is your new album launch coming on 26 November?

When I started Most Dismal Swamp, I was still feeling around to make sense of what it was and could be. In some ways, MDS is a platform, such as in the part of it that operates as an independent music label and as a channel for the ongoing series called Dismal Sessions.

However, it is also largely functionally, not a platform. It is more of an artistic-curatorial project enriched and guided by various collaborations, commissions, research holes, experiments, and dank immersion. I feel like it is appropriate to think of it as something more dynamic and contingent, like a biome, a multi-reality biome.

This is reflected in the sounds that emerge from the MDS label – it is very eclectic and follows no specific genre or sound. I am just interested in indulging the part of me that is an unapologetic fan of some art and music. And as a fan, it is possible to extrapolate and see the strange worlds indexed by the artefacts you adore.

The next release is by the Leipzig-based producer and designer MYEN. Their album is called NEODORSAL. It is a sound I find hard to define, and it offers me something new with each listen, feeling as if I am listening to something at once extremely abrasive and deeply personal. NEODORSAL is also an exploration and application of MYEN’s creation of an artificial larynx that functions as their post-organic vocal instrument, creating an unusual vocal palette throughout the album.

What makes this release all the more exciting is that it will also be the first physical release on MDS and a digital album; it will also be available as an engraved USB with additional artwork and a 3D-printed wearable nosepiece. Furthermore, it is also the first time I have organised a launch party for a music release. This is a night of music hosted by Hackney venue The Glove That Fits, with some of my favourite DJs and producers as guests: KAVARI, Terribilis, Ship Sket, and SWARMM.

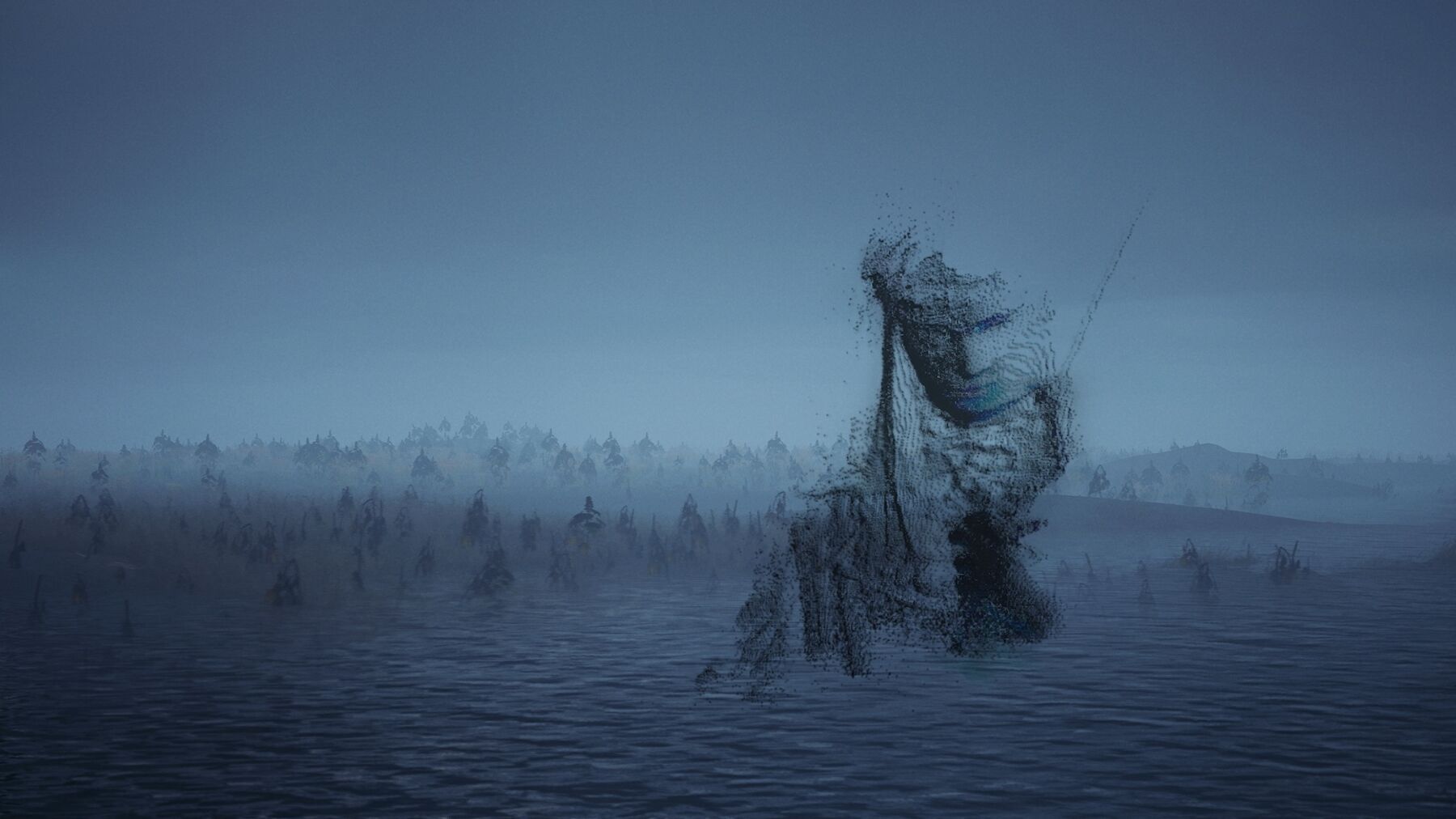

Your current 360-immersive screening MUSH is showcased at MIRA in Barcelona- what can we expect? With a name that comes from Multi-User Shared Hallucination, a term derived from the field of online text-based role-playing games, tell us a bit about the intellectual process for its inception.

MUSH is presented with a 360-degree film projection across four walls and floors, measuring 23m x 21m x 6m. So it has been a fun and interesting challenge to make something to this specification. Filmed sequences that feature various artists’ sculptures, CGI, garments, etc., are housed in virtual ‘screens’ in a dynamic 3D environment developed by artist Samuel Capps. In addition, it features new music by FRKTL along with narration written by me.

With MUSH, I was keen to exemplify a dense body of opaque rituals, gestures, theories, protocols, interactions, and imagery that would be like coming across some strange shitposting account or conspiratorial blogroll where you were not quite in on it; where the dog-whistle transmission is meant for some occult online community.

So the film contains footage of unnamed groups of people coming together in some underground and derelict space, building an elemental shared language together across intimate gestures, tentative interactions and arcane memetics. On the one hand, I am interested in exploiting a heavy, dense ambience to create an immersive experience that enables a sense of peering into the life of a sub rosa para-social community (like when I first came across the now-defunct CCRU website in 2009).

And on the other hand, I was also keen to try to depict and embody the subjective experience of being immersed deep within a MUSH, or some unorthodox pipeline that is buttressed by communal investment in the rhetorics, protocols, beliefs, etc. that render it as distinct from an ‘outside’ mainstream – a shared gamespace that feels like its own world.

Therefore I have continued an exploration of what it means to be deeply immersed in one reality at the expense of being deeply detached and disassociated from another; what it is to create and inhabit alternative roles, to construct a language, to ‘build an ideology’, to LARP a social contract, to instantiate a heresy.

Many of these concerns emerged and were explored during the 2020 national lockdowns. With the closure of public venues and the looming possibility that they may not receive the support required to remain open after the lockdowns (and even if they did re-open whether culture would become further stratified by increased door prices and post-pandemic restrictions).

I wondered if we were likely to experience a greater sense of social Balkanisation as communities bonded by institutional mistrust would ferment in private spaces.

Moreover, what were you exploring more at the technical level? The project feels like a complex matrix with work from several multidisciplinary collaborators; what were the challenges of unifying the different individual’s aesthetics or narratives into the same project?

Primarily different ways of exploring immersive experiences along with compositing the diverse works and worlds of artist collaborators. MUSH makes use of the opportunity presented by MIRA Festival to work with the resources and technical experts of the venue Ideal Barcelona.

Given the proposed format they offered, I shared my idea for presenting MUSH as a life-size version of a virtual environment with embedded screens with artist Samuel Capps. Samuel worked from some loose ideas I shared but then worked for weeks on developing an environment built using Unreal Engine 5 that surpassed expectations and enabled the project to further explore the mingling of artists’ works (the environment also contained animated 3D figures by Olia Svetlanova and images by Tissue Hunter and Lou Shafer that we installed as wall decals.

In these examples alone, there is a combination of being entrusted by the collaborators to implement their work in an unexpected way (which is so different from receiving an artwork for a gallery exhibition along with specific installation instructions), and also in working with someone like Samuel who can open up the possibilities of software like UE5, enabling new ways of unifying works to become intuitively apparent.

There is also an understanding in such projects that unlike the modernist mode of gallery presentation characterised by contemplative distance, MDS projects embrace a more immersive and intimate method whereby it is sometimes difficult to see where some works end and begin and that they may not be presented in an entirely equal footing where they are allowed to share their full ‘narrative’ – they are enfolded into the action of the swamp. Yet, their presence also expands and mutates the overall experience of the project.

I also grew up listening to noise music, and I still appreciate stuff like the early Slipknot albums where a virtuosic wall of sound invites repeated appreciation of granular details. This seems to have influenced my approach to creating densely compressed artefacts or scenarios – thickly tangled swamps of information that I hope people will return to find new details and patterns.

Most Dismal Swamp collaborated extensively with Gossamer Fog art space in Deptford during London lockdowns – what was your curatorial experience?

The project I developed with Gossamer Fog over one of the lockdowns was a ‘virtual production live stream called Creep Vector. This was kind of a curatorial experience, but not entirely. Samuel is the director of Gossamer Fog, so again, in this situation, we could work closely together, and his knowledge and optimism enabled me to inhabit an artistic and directorial role.

The setup consisted of a purpose-built green screen studio and a live camera feed connected to a virtual reality sensor that mapped the recorded image into virtual environments built using Unreal Engine 4.

Once again, Samuel offered his expertise and resources to place me in a position where I could direct the construction of a virtual environment, how it was shot, and how Creep Vector will be presented (and also allowed me the chance to learn a great deal about this form of production).

Ultimately, we created virtual scenes with digital assets by artists such as another regular collaborator Hannah Rose Stewart and composited live performances by Laila Majid, guia, and Jame St. Finlay. It was a highly ambitious and fun experiment, especially considering that these production techniques are pretty much only really achieved by high-end industry professionals.

Last summer, you contributed a crucial background research to the SWAMP installation at Berlin’s Berghain- what did the research entail?

Jakob contributed some of his VR material to the first MDS project, ‘Swamp Protocol’, and soon after, we also discussed some of the swamp-related research that I pursued. So it has been extremely pleasant to be involved with his work and share some ideas on this topic again. Jakob’s project ‘Berl Berl’ was a sprawling beast that touched so many ideas and subjects, even just from focusing on the swamplands and history of the Berlin locale.

While he engaged numerous collaborators, including specialists in the fields of animal and plant life he came across on his field trips, I worked with Jakob and the Light Art Space team in unearthing some cultural artefacts (images, poems, songs, stories etc.) that related to the wetlands of Sorbian culture from which Berlin receives its name.

This was another opportunity to really enrich my understanding of how swamps have impacted the everyday life and mythos of cultures and made their mark on peoples’ language and art by focusing on a specific ecological niche.

What would be your biggest curating extravaganza?

There are four things I would find hard to top but would certainly influence my planning of a Big Curatorial Extravaganza:

- The deceitful inclusion of enormous Sports Direct mugs in the shopping baskets of everyone who purchased goods via the SD website.

- The deceitful permanent installation of the album Songs of Innocence by U2 on all iPhones in 2014.

- The Hellraiser VHS that appears on one of the bus stops on Old Kent Road.

- The vibe of TV Party.

What’s the chief enemy of creativity?

I find that the uncritical inheritance and propagation of empty rhetoric and anachronistic terms to really impede creativity in our scenes and networks. If I have people to talk to and access cans of Monster, I can work creatively – it is a social pursuit, I think.

So when the mannerisms and tropes of past orthodoxies still mould creative thought and action, I become aware of the critical and speculative labour involved in fulfilling Benjamin Bratton’s proposal that “we need new models”.

The language, concepts, images, models, and methods we employ act as a form of cognitive scaffolding, presenting creative affordances and contingencies. So this is why I am invested in working out a composite logic of the swamp as a model for making better sense of the binaries that persist in our discourse, such as online/offline, reality/fiction, etc.

When we think about the terms being used, we can understand the limitations and opportunities they present for creativity, rather than peppering our optimistic pitch decks and press releases with the same handful of buzzwords that merely signal rather than create meaning.

I was always sceptical of the rhetoric that couched the revolutionary achievements of art’s social turn (The Long 90s), and now amid a speculative turn, I remain jaded by the jargon, vagaries and diagrams of interactive/speculative design about worlding, making kin, complexity, etc. These practices usually end their communique with calls for making a better world, but they evidently can’t even make their own critical vocabulary.

Just so I don’t end on that bum note, I’ll say that I think the chief ally of creativity is having a massive laugh: for the lulz, as they used to say.